By Anna Tsekani,

Nowadays more and more people shed light upon topics that in the past were not only taboo, but also people were not so familiarized with. Postpartum depression is one of those topics.

Depression is one of the most disabling disorders for women during their reproductive years.

PPD (postpartum depression) is a serious mental health issue which is prevalent, and offspring are vulnerable to developmental disruptions.

Postpartum Depression is strictly defined in psychiatric nomenclature as a major depressive disorder (MDD) with a postpartum onset within one month of childbirth. Yet, in several research and clinical practice, postpartum depression refers to depression that occur during the postpartum period, which is increasingly defined as up to one year after childbirth.

However, depression in women during the postpartum period can also easily begin during pregnancy or occur after the first postpartum month.

The term “postpartum” refers to the period following childbirth. Postpartum depression is a serious mental illness that affects both your behavior and your physical health. If you feel empty, emotionless, or sad all or most of the time during or after pregnancy, or if you don’t love or care for your baby, you may have postpartum depression. Depression treatment, such as therapy or medication, works and will keep you and your baby as healthy as possible in the future.

Past depression, stressful life events, poor health, marital relationships as well as social support are all major risk factors. In terms of total disability, it is second only to HIV/AIDS for women aged 15 to 44 years worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2001).

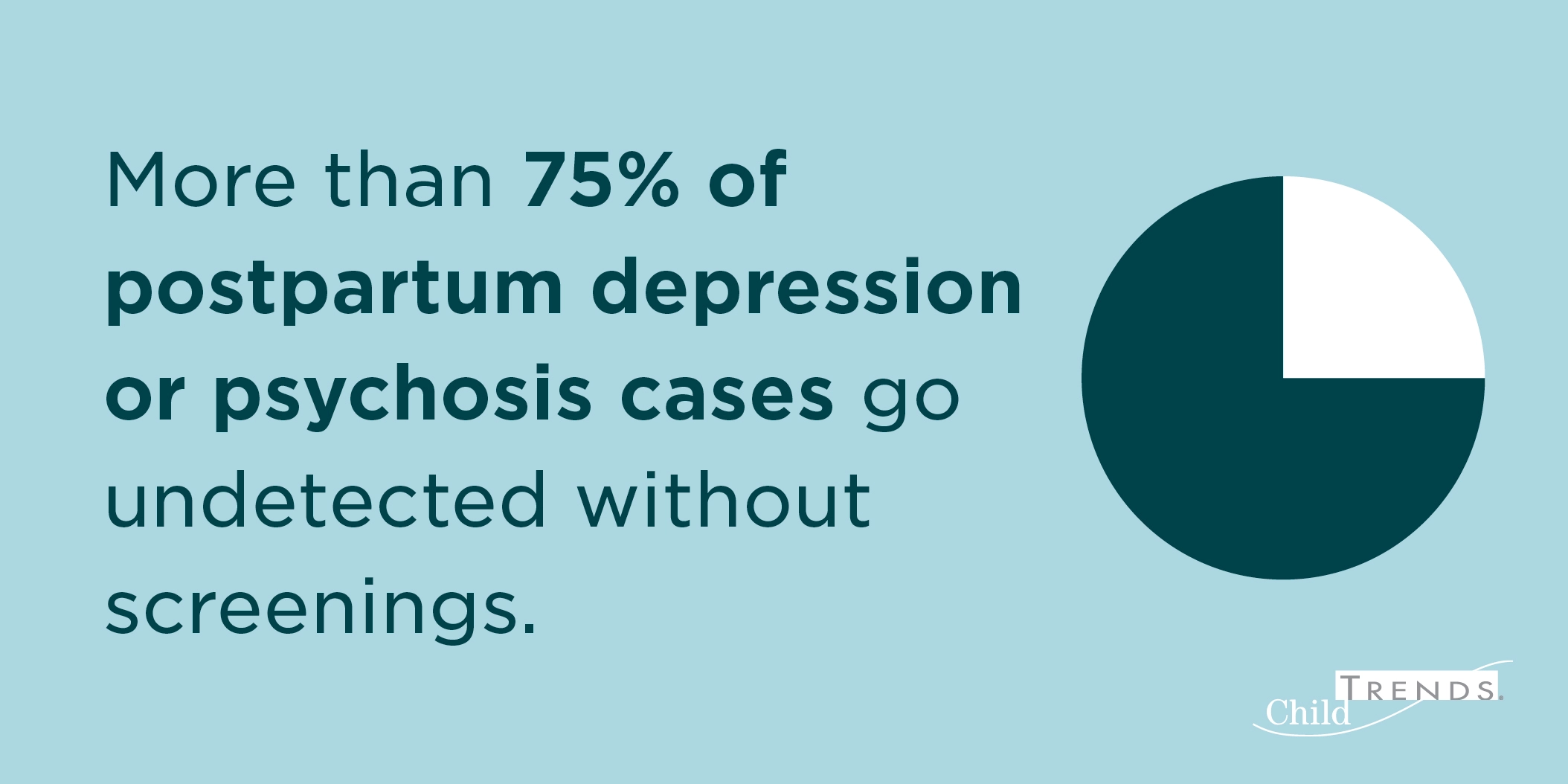

Statistically, up to 15% of mothers suffer from postpartum depression (PPD). Several psychosocial and biological risk factors for postpartum depression have been identified in recent research. The detrimental short- and long-term effects on child development are well documented. PPD is both underdiagnosed and undertreated and due to this find, a small number of researchers have shed light on this topic. Obstetricians and pediatricians can play important roles in detecting and treating PPD. both in mothers’ and in children’s lives.

Though, the link between untreated maternal depression and impaired child development is well–established and known. PPD is associated with a higher incidence of excessive infant crying or colic, sleep problems, and temperamental difficulties in infants and children. Infant crying and sleeping problems may increase the risk of new–onset PPD, but they are also more commonly reported by women with postpartum depression.

Postpartum depression could be associated with a difference in sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations. In comparison to healthy control subjects, euthymic women with prior PPD experienced dysphoria after the addition and withdrawal of supraphysiologic doses of estradiol and progesterone. Biological theories have included fluctuations in other gonadal hormone and neuroactive steroid levels after delivery, altered cytokines and HPA axis hormones, and altered fatty acid, oxytocin, and arginine vasopressin levels, in addition to sensitivity to estrogen and progesterone fluctuations.

In the largest PPD meta-analysis to date, the global prevalence of PPD was found to be approximately 17.22%. The study’s findings revealed significant regional differences, with Southern Africa having the highest prevalence rate: 39.96%. Furthermore, country development and income disparities had a significant impact on PPD epidemiology. The prevalence of various variables such as marital status, educational level, violence, partnership, life stress, smoking, alcohol use, and living conditions was discovered to differ significantly. However, there was no significant difference in PPD between infant gender and gender preference.

Major depression causes suffering whether it occurs during the postpartum period or at any other time in a woman’s life. Childbirth is culturally celebrated, and new parents are expected to be joyful, if not exhausted, during this time. The demands on a new mother are significant, including providing 24-hour care for a newborn, often in the middle of the night, maintaining normal household responsibilities, and frequently returning to work after a brief maternity leave. These burdens are frequently difficult to bear in normal circumstances, and the difficulty is exacerbated by the disability associated with depression symptoms.

“It’s really important to acknowledge and normalize that going from an independent adult to someone’s parent is not something that happens in the blink of an eye.”

Psychotherapy and antidepressant medication are two treatment options. Access to psychotherapists and breastfeeding mothers’ concerns about exposing their infant to antidepressant medication are barriers to compliance with treatment recommendations. Yet, more research is needed to investigate the short- and long-term effects of medication exposure via breast milk on infant and child development.

Through the passage of the years, public health efforts to detect PPD regarding in women and children are growing. Studies of epidemiological risk factors and prevalence, interventions aimed at the parenting of PPD mothers, specific diathesis for a subset of PPD, effectiveness trials of psychological interventions, and prevention interventions aimed at addressing mental health issues in pregnant women should all be part of future research. At the same time, it is significantly important to address the issue also among men: fathers may also suffer from such issues on their own or be affected by women’s of child’s depression.

References

-

O’Hara, M. W. (2009). Postpartum depression: what we know. Journal of clinical psychology, 65(12), 1258-1269.

-

Pearlstein, T., Howard, M., Salisbury, A., & Zlotnick, C. (2009). Postpartum depression. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 200(4), 357-364.

-

What is postpartum depression, unicef.org, available here

-

Postpartum Depression Increased During Pandemic’s First Year, newsroom.uvahealth.com, available here