By Katerina Dimarogkona,

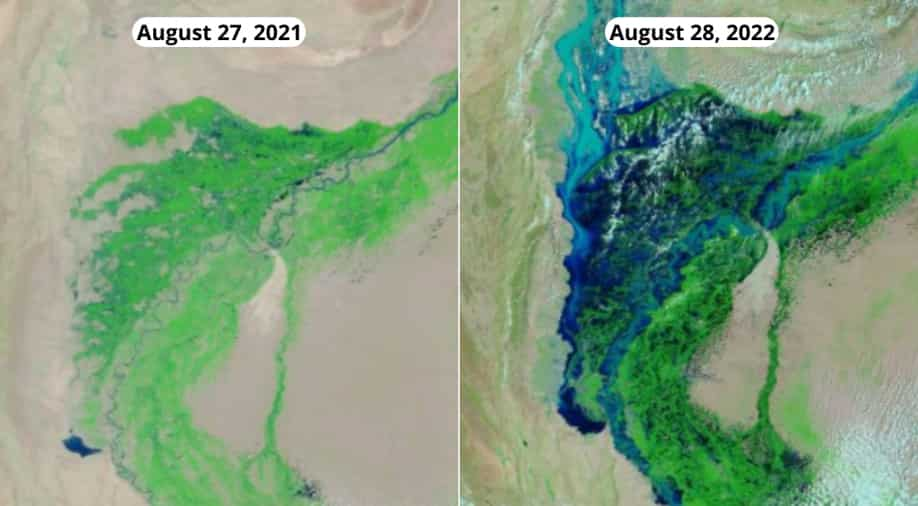

A third of the country of Pakistan has flooded. It is seeing more than 30 million people leaving their homes en masse, a million of those homes destroyed and mourning over 1,000 of those who did not survive the disaster. By no doubt, the most dangerous climate disaster it has experienced in recent decades, the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths is calling it “the world’s worst climate nightmare” and is making demands for climate justice for the Pakistani people. And if a nightmare, it is one that is over the years being repeated more and more often, with ever greater intensity.

When I asked about the effects of the floods, a Pakistani woman studying in Europe, said: “This has been happening every couple of years for the past decade. People ask if my family is safe, and the truth is I do not know. I do not even bother to check with them anymore, floods have become so common”.

It is a paradox that in a country with almost a desert climate such floods would be a problem. Climate change indeed poses a grave danger for its economy, agriculture, and mortality rate. In 2020, Pakistan was rated fifth in the world on the Global Climate Risk Index, a list of countries most vulnerable to climate catastrophe. And while climate science never speaks in certainties but in statistical probabilities, the evidence suggests that Pakistan is probably so vulnerable compared to other countries because of its geographical location, the socio-economic status of its citizens, and a general lack of infrastructure.

For one, there is more moisture in warm environments while South Asia has been warming faster than the world average, at 0.7 Celcius since 1900. For every degree, the atmosphere warms humidity rises by 6-7%, and humidity means the greater intensity of rain will be during monsoon season. The other side of that coin is that when there is more intense rain during monsoon season, there is also more drought for the rest of the year.

The extreme heatwaves that hit Pakistan reached 50 degrees Celcius this year, the hottest worldwide, causing a thermal low in the region, which increased the probability of a highly destructive monsoon season. Experts earlier in the year predicted that the effects of climate change were a deadly heatwave 30 times more likely to happen.

Pakistan is also home to about 7,000 glaciers in its mountains, the largest number on the planet outside of polar regions. This fact, coupled with the extreme heat observed, has resulted in the extremely fast melting of this ice, which amplifies flooding in the area.

And then, a phenomenon as complex as monsoon is influenced by a variety of factors, one being the la Nina phenomenon in the Pacific, which brings great winds of moisture to the Himalayas. When they happen at the same time, as happened this year, this extreme phenomenon compounds with Pakistan’s already unstable weather patterns and increases the chances of destructive weather.

However, this is not even the whole story. Because extreme weather phenomena get all the media’s attention, we are ignoring a whole other climate-related health crisis that is going on. Illnesses like lung cancer and asthma are rapidly on the rise, while pneumonia is the primary cause of childhood mortality. Factory emissions, traffic emissions of cars that burn dirty fuel, and people burning coal for food and warmth are driving this rise in respiratory diseases.

At the same time, mosquitoes, a rise in the rodent population, and contaminated water spread malaria, leptospirosis, and dengue fever widely. The floods are to blame, and the country’s lack of infrastructure when it comes to sewage, resulting in water becoming a source of disease. Malaria is as prevalent as 22% of the population in certain parts of Pakistan.

When talking about these problems, we should be always aware of the uncomfortable fact that Pakistan cannot manage on its own these crises it is facing. People use dirty fuel for their cars because the government cannot fund a clean fuel program. There is no money to prevent large-scale destruction of property in the case of floods. And while Pakistan produces less than 1% of the world’s emissions, it is forced to bear the brunt of our fuel-intensive way of life in the west, able to do nothing while its glaciers are dangerously melting, and monsoon season becomes a hazard to human life across the country.

The unfairness and the uneven effects of climate change on different parts of the world are evident, and often the countries most affected, the ones with the most polluted air and water are also the poorest, which cannot take large-scale measures to protect themselves. This leads to a sort of “outsourcing of pollution” where we for example produce goods in countries with very little if any environmental standards, leaving them to face the consequences. Fortunately, there is talk of a $1.2 US billion aid package for Pakistan being negotiated by the UN, which is some sort of a first step.

All of this points to what the Pakistani woman I talked to said: “While the West is debating whether climate change is real, we are living the effects of it today”. And it is true, that our conversations focus on replacing plastic straws with paper ones, greener energy, and the possibility of better technology fixing all our climate catastrophe problems. The answers we give to the climate crisis seem ridiculous and superficial in light of the sheer destruction countries like Pakistan are seeing. We are missing the point. It might be Pakistan today, but it is us tomorrow.

References

- The Guardian view on climate chaos in Pakistan: adapt to survive, theguardian.com, Available here

- Why are Pakistan’s floods so extreme this year?, nature.com, Available here

- Pakistan floods: Biggest lake subsides amid race to help victims, bbc.com, Available here

- Pakistan floods: what role did climate change play?, theconversation.com, Available here

- Impact of climate change on health in Karachi, Pakistan, sciencedirect.com, Available here