By Penny Theodorakopoulou,

What is the cause of the creation of everything? Who or what created the world we live in? How was the world created? These and even more questions have been attempted — and succeeded — to be answered by thousands of researchers from one end of the world to the other. The creation of the world has been a rather controversial and complicated issue since the time of our ancient ancestors, a topic that prevails even to this day. From The Big Bang Theory and Galileo to the ancient Greek philosophers to the Christian church, the question of the creation of the world has taken many forms.

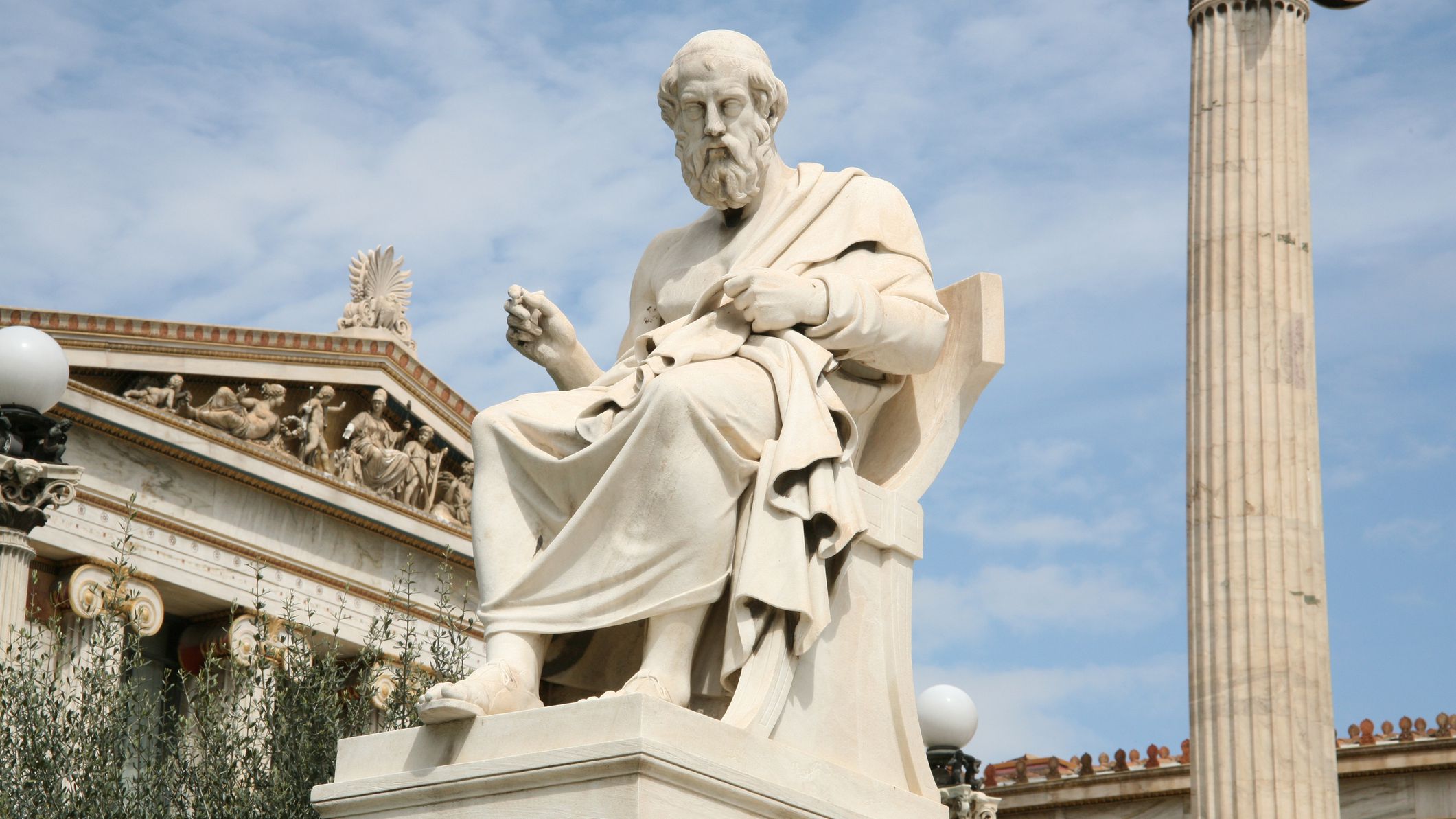

One of the many intellectuals that talked about the creation of the world was Plato. The ancient Greek philosopher dedicated an entire dialogue to the subject we are concerned with, named Timaeus (c. 360 BC). Named after the eponymous astronomer and physicist of Plato’s time, this dialogue is influenced by the teaching of the pre-Socratics, who explored questions such as those mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Although Timaeus is the only Platonic dialogue devoted entirely to who and how the world came to be, we find a small reference to the same theme in Plato’s dialogue the Statesman (c. 366-362 BC), which is about the inverted circles of the world (we will further explain that on Part II). Other references to the creation of the world can be found in the Sophist (c. 360 BC) and the Philebus (c. 360-347 BC).

The creation of the world in Timaeus: The Platonic god-Creator

As said above, the Platonic dialogue Timaeus is not an ordinary dialogue written by Plato. From the form to the theme and the characters of the dialogue, Timaeus is a dialogue that is very special. The subject of this particular dialogue is, as we mentioned above, the creation of the world. Who created the world and how was it created?

The answer to the first question is given by the very first lines of the dialogue, where the Platonic Creator is spoken of. The first thing mentioned about Plato’s Creator is that he is identified with the becoming (γίγνεσθαι), which is its cause. Thus, the cause is automatically transformed into a creator, while the becoming (in the sense of constant change) deals neither with the principle of change nor with the cause. What deals with these issues is the product something, which with its introduction, reveals the structure of the image of the exemplar, that is, the image of the perfect thing, from which the Platonic god-Creator will be inspired and will create the rest of the beings according to his image and likeness, and the structure of the Creator.

Starting with the narration of the myth regarding the creation of the world, the protagonist of the dialogue, Timaeus, brings to the table the world generally. He claims that the world is visible and tangible, which is why it belongs to events. The world, he adds, has a cause, a creator. At this point, we must note the following: the world was not born suddenly, there was pre-existing material, which is an indeterminate becoming, without a cause — without a creator, in short. The creator “takes” this indeterminate becoming and processes it, creating an orderly world out of a disordered world.

The reason that the creation of the world originates from antiquity is the opinions of various researchers differ from each other. Physiologists today argue that the transformation of the universe and the world takes place in a natural way, a view that opposes the image of the Platonic god. According to Plato, the god is within the world and acts within it; however, the opposite cannot happen, that is. The world cannot act on the god-creator. Because god interacts within the world, Plato also considers the world to have a soul, and therefore a mind. Thus, the cause, that is god, is constantly at work in the world. Timaeus then quotes that the god of the universe is hard to find, even if he acts in it.

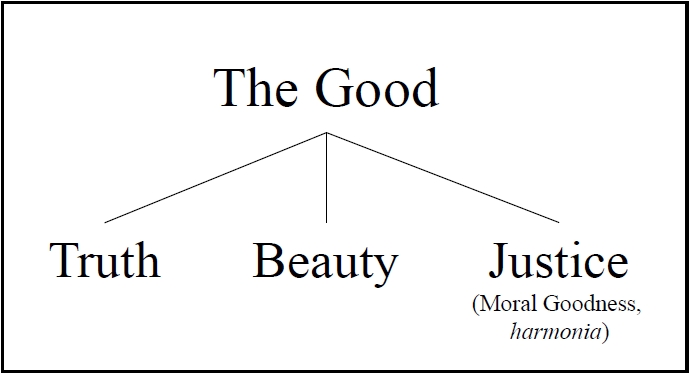

But even if the world could appear, it would be impossible for it to appear to all mankind. But in addition to being a craftsman, the Platonic god is called (in the dialogue we are examining) a poet, a father, an excellent cause, good, and — of course — a god. In addition, he appears to think, desire, rejoice, and speak. It should be noted that the Creator is not omnipotent; he has good intentions and unlimited mathematical abilities, but his work must have limits and be inferior to the real possibilities. Finally, it does not create out of anything and produce anything new: it contemplates and organizes matter with knowledge, imposing rules of order and beauty, as it implements the eternal pattern.

The divine Creator: How did he make the first being?

As we mentioned above, the Platonic god-Creator is good and has goodness in him. The end result of the world in which we live and act is “the infusion of the good nature of the Creator into his creation, which is achieved by imposing order upon disorder”. The Platonic Creator perceives that order and beauty in the aesthetic/sensible world are equivalent to the existence and mastery of the mind. Based on this, he considers that as visible, the world will have a body and, in order to be the perfect creation, it must also have a mind, therefore a soul. At this point, the Creator wants to give meaning to the world in action, and he will achieve this through the creation of an animated and rational being: man.

Although the Creator constructs other things besides the world, his main work is the shaping of the body of the world and the construction of its soul. Having this as a basis, we can say that everything else he does in the world is a simple modification of the above activity. For the time being, we can establish the world as follows, as well as add some elements: it is unique, complete, contains all four elements of nature, does not get sick or grow old, has a perfectly spherical shape, and does not consist of organs and limbs. However, the features of the Platonic world that we have just listed do not all come from the Creator, such as health and youth. These are due solely to the total use of the four elements of nature, while the absence of members gives the world its perfectly spherical shape, the youth of space, and so on.

After forming the world, the Creator moves on to the second part of his master’s work, the building of the soul of the world he created. According to Timaeus, the soul, being invisible and existing in both ontological realms (meaning the aesthetic/sensible and the conceivable world), is quite difficult to construct, for the main reason that it does not have any conceivable model, as in the case of the soul, rational being. After an extensive and rather difficult process, which Timaeus never reveals to us, the soul adapts to the world, rotates around it, and makes it eternal. Since the world of the Creator now has a form and a soul, it is worth devoting a small passage to mental functions. According to Timaeus, these are two: the production of knowledge and the production of movement. The soul, having these two functions as a “helper”, must succeed in acquiring the mind, that is, in acquiring truth, as well as the world now having a smooth rotational movement.

Since we have discussed the divine creator, it is time to add the mortal creator. A creator is, essentially, a professional craftsman. Therefore, Creator is the craftsman of antiquity. After the passage from Plato’s dialogue the Gorgias (c. 380 BC), we observe the following similarities between Gorgias’ craftsman and Timaeus‘s Creator: initially, both act with a purpose. They do not do projects just for the sake of doing them but have a plan, which they follow to the letter and consistently. Both of them want to give shape to what they will create by envisioning a specific model-vision. In addition, in order to perform the task, both use materials that already exist, which project some resistance to their action. Finally, they use the components in the best possible way, with the end result that their creation has order and peace (κόσμον).

We notice that both have several similarities. But no one is the same. Gorgias’ craftsman will use violence anyway, unlike Timaeus’ Creator, who aims for persuasion. Taking the latter as an occasion, the rational Creator does not need violence, so he cooperates with Necessity through persuasion. Without special and thorough analysis, we can say that force and persuasion are completely different things. But if we study them in detail, what we will notice is that they are not that different. In both direct force and indirect force (persuasion), the archaic metis appears. It is the clever artifice, the scheming, the deception. In Timaeus, mῆtis is not mentioned anywhere, but it is implied by the works of the Creator: he can cause mῆtis only by being a craftsman because only then does he try to manage the materials and ultimately create strategies.

In the next part, as we referred to above, we will explain the inverted circles of the world, as they are presented in the Statesman.

References

- Πλάτων, Τίμαιος, εισαγωγή – μετάφραση – σχόλια Βασίλης Κάλφας, εκδόσεις Εστία, Αθήνα, 2016, Πέμπτη έκδοση.

- Timaeus (dialogue), wikipedia.org, Available here

- Plato’s Timaeus, plato.stanford.edu, Available here

- Plato’s Cosmology: The Timaeus, faculty.washington.edu/smcohen, Available here

- Taran, Leonardo, The Creation Myth in Plato’s Timaeus (1966). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 252, orb.binghamton.edu, Available here

- Plato: The Timaeus, iep.utm.edu, Available here