By Socratis Santik Oglou,

It is quite difficult to understand how cultural theory and psychoanalytic theory interact. Insofar, as they are both curious about the purpose of social life and the necessity of their ermines, there are obvious similarities between them. But the gap between these theories is growing due to two factors. First off, psychoanalysis is less interested in societal processes and more focused on the psychopathology of the individual. Second, a predisposition toward psychological and biological reductionism distinguishes much psychoanalytic thinking. One of the greatest contributions to the cultural theory of the 20th century was the work done by some psychoanalysts to remove these boundaries. In fact, these initiatives have influenced modern culture to the point where it is frequently difficult to tell psychoanalysis apart from cultural theory. Nevertheless, we will refer to Sigmund Freud’s work in this article.

Freud was born in Freiburg im Breisgau, close to the borders of Germany and Czechoslovakia, but his family relocated to Vienna when he was still a child. He did well in school and graduated with honors. He entered the University of Vienna’s Medical School in 1873. He received recognition for his work on the study of hysteria and neuroses while visiting Paris. He focused almost entirely in the 1890s on hypotheses that opposed then-prevailing beliefs and held that mental disease was caused by mental rather than bodily causes. He also wrote about a variety of other topics at the same time, including phobias, sexual dysfunction, and dreams. All of this was described as the result of a rich and intricate unconscious, whose primary components include dreams, fantasies, and impulses. He had to flee London in 1938 to avoid being detained by the Nazis. In 1939, Freud overdosed on morphine, which he had expressly requested the doctor give him.

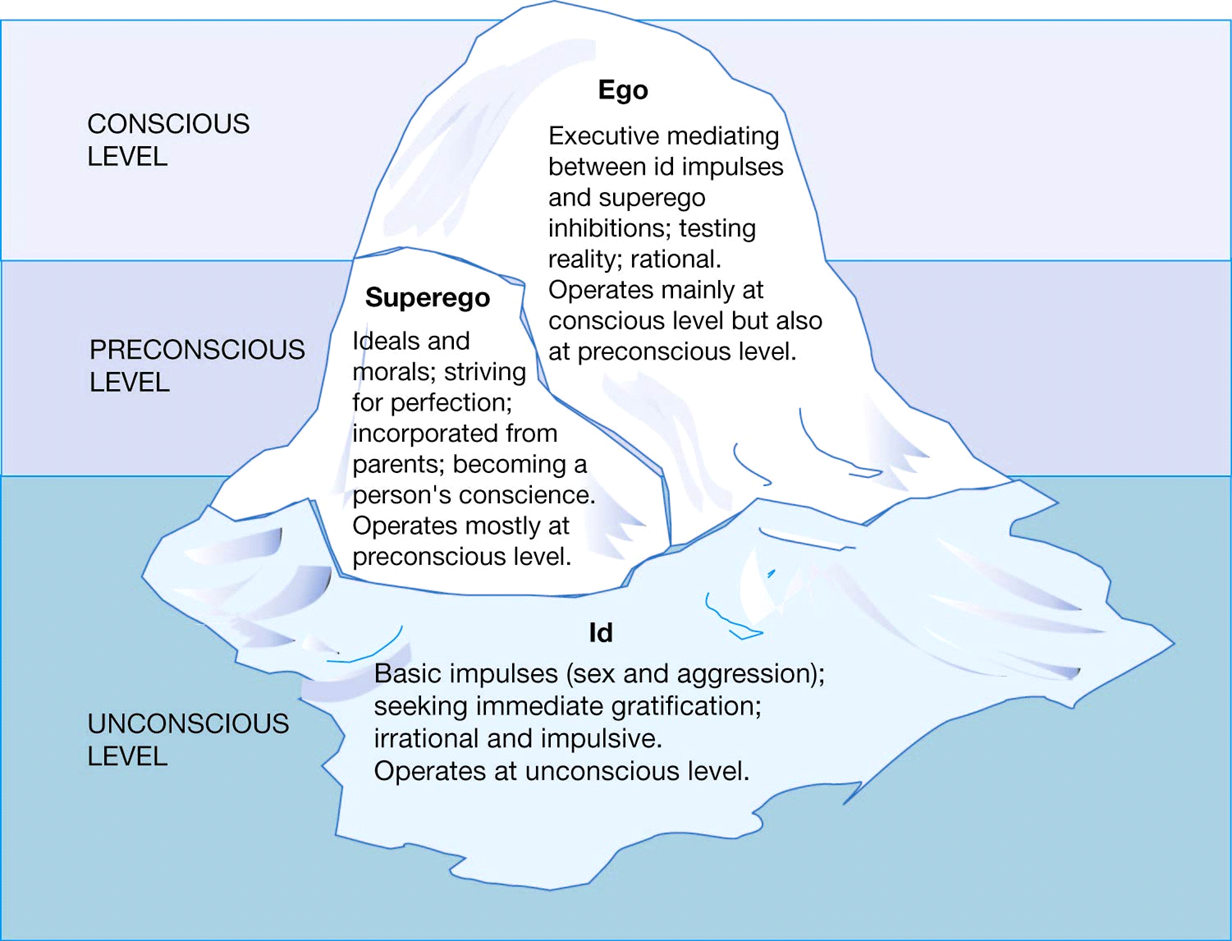

The idea that we are what we perceive was rejected by Freud. He holds that our identity, personality, and mental processes are therefore more intricate than we can possibly comprehend. The gap between the aware and unconscious was then hypothesized to exist. The interplay between these two psychic locations is ongoing. Another distinction made by Freud states that there are three levels to the human soul: the Self, the Ego, and the Superego. As opposed to specific regions of the brain, these phrases primarily refer to features of the mental organ. The desires that demand instant gratification reside in the Self (Id). The ego accepts reality while performing an act of self-crucifixion. He is the leading representative of common reason and rational speech in this regard. While the Superego is the core of morality and consciousness. The family in particular and society — in general — are the sources of the Superego.

According to Freud, the self should be viewed as a system whose fundamental component is sexuality, which is intimately connected to the pleasure principle. He constantly strives to state his own urges, which have their source in the Self. Sexual pleasure is directly correlated with impulses. Infants are able to satisfy themselves while also stimulating diverse body areas (the corpse through the follicle, the genetic organs through urination, and later through friction). However, as we mature and develop a sense of self, we are forced to exert control over those impulses. However, this repression of these urges to the weak leads to the development of neuroses, perverse, obsessive psycho-psychotropic syndromes, and a variety of other psychopathological disorders.

Freud claimed that the need to continually suppress one’s sexual urges makes much of modern life, both individually and collectively, intolerable.

One of the most significant repressed drives, at least in men, is connected to what Freud called the Oedipus Complex. An old Greek story in which Oedipus kills his father and weds his mother gives this complex its name. Boys are drawn to their mother, in Freud’s opinion, mostly because she can provide for their desires in terms of their sexuality in general. However, the existence of the powerful and authoritarian father prevents them from being united with the mother, which causes them to be overcome with feelings of rage and yearning for the mother as well as the dread of being castrated.

Freud spent a lot of his clinical time analyzing different psychopathological patients. But in his later writing, he employs psychoanalytic theory to investigate neurotic cultures. As he abandoned his sexuality model and developed the bipolar Eros-Death (Life and Death Drives), which holds that the lover represents sexual intuition, kisses, love, and creativity, while death represents aggression and destructiveness, he also continued to turn a blind eye to his gallery at around the same time. The greatest significant effort by Freud to examine culture as a social phenomenon is found in his 1961 Allied book Civilisation and its Discontents.

According to Freud, there is a parallel between how the subject grows and how culture does. In both situations, the conscious self must take charge of the impulses in order to maintain a normal personal and social existence.

According to Freud, there is a stark contrast between the impulses that call for instant pleasure and the needs of culture for order, cooperation, and control. More specifically, he writes: “It is impossible to overlook the genome that to a large extent culture is founded on the repulsion of the orbital material and the rejection of unmediated enjoyment. This cultural frustration largely determines people’s social relationships”.

Freud places a special emphasis on the ways that impulses are resisted or altered. In the second instance, people turn to areas that help culture evolve, like employment or family love. However, because this process is rarely finished, modern people are frequently overcome by guilt, discomfort, and violence.

References

- Freud’s Theories of Life and Death Instincts, verywellmind.com, Available here

- The Freudian Theory of Personality, journalpsyche.org, Available here

- Freud: Id, Ego, and Superego Explained, greelane.com, Available here

-

Philip Smith, Cultural Theory – An Introduction, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, 1st edition, 2001