By Penny Theodorakopoulou,

Imagine a world where you could truly be yourself. A fantastic world where your imagination is your friend and enemy at the same time, depending on how vast your imagination is; a world filled with magical creatures, spellcasters, and, of course, dragons. To a person who plays video games nowadays, this is no news, but rather their daily routine, be it in casual open-world RPGs (role-playing games), indie games, or MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games), where everything is possible. But for someone who was awed by the video game industry back then, they felt like they were really not themselves while playing a game, for instance, Super Mario Bros.

The latter changed in the mid-70s. To be specific, in 1974, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson were the pioneers of a new type of game, where you could be anything you wanted. A game where, for the first time in human and game history, you could play as a character you chose. The game: Dungeons & Dragons, D&D or DnD for short. D&D is the first known fantasy tabletop RPG that was ever created. The concept of D&D is quite simple: there is a group of people (ideal number: 3-4), each of whom is playing with the character they created. That group follows the story that the Game or Dungeon Master (GM/DM), who is describing everything the players see in a fantastic setting. Then, when a decision must be made, it is the party that decides what to do, according to their characters’ alignment. The goal of the game: to complete the story without the party dying, of course.

Lawful Good vs Chaotic Evil: The alignment system of D&D

Each of the nine categories (Lawful Good – Lawful Neutral – Lawful Evil; Neutral Good – True Neutral – Neutral Evil; Chaotic Good – Chaotic Neutral – Chaotic Evil) is some combination of the following four values: from left to right, it goes from law to chaos, and from top to bottom, it goes from good to evil. The alignment chart above, whether you love it or hate it, is, nonetheless, a foundational part of the game. What does each of the categories above mean, though?

- Lawful Good (LG): A protector is a lawful good character. A paladin, a holy knight who protects the vulnerable and eliminates evil, is the archetypal exemplar of lawful good.

- Neutral Good (NG): A decent neutral character prioritizes generosity above anything else.

- Chaotic Good (CG): The ultimate virtue for a Chaotic Good character is freedom. Robin Hood is a classic example of chaotic good, rebelling against authority in order to defend the underprivileged from poverty and pain.

- Lawful Neutral (LN): As the ultimate virtue, a legal neutral character obeys principle. A judge who treats everyone fairly and equitably, for example, would be deemed legal neutral.

- True Neutral (TN): A truly neutral character is unconcerned with any alignment attitude on both axes. This is commonly used to characterize someone who is simply concerned with their own demands and is not willing to damage or harm others, obey, or revolt. A few truly neutral personalities, on the other hand, adhere to a deliberate ideology of balance. Mordenkainen, an archmage on the world of Oerth, is one such example, who utilizes his immense power to preserve the status quo and prevent any single entity from growing too dominant. Gary Gygax, one of the creators of D&D, favored this concept of pure neutrality.

- Chaotic Neutral (CN): A chaotic neutral character will follow their heart, but not to the extent that a chaotic good character would. Many adventurers are chaotic neutrals who do as they choose while rejecting all forms of authority. Some chaotic neutral personalities have made it their mission to demolish the old, in order to make room for the new.

- Lawful Evil (LE): A tyrant is a legal wicked character. They have no moral qualms about punishing people in the name of society’s advancement. A lawful evil villain is typically simple to deal with since they can be relied upon to uphold their promise.

- Neutral Evil (NE): A neutral evil character is self-centered, and would damage others to achieve their goals if they can get away with it.

- Chaotic Evil (CE): The true definition of evil. This alignment might be seen in a vengeful villain. Whereas the most powerful lawful evil villains may seek to dominate the world, this may be preferable to their chaotic evil counterparts’ goal of destruction, seeking the absolute chaos in the world.

In other words, while creating the character, the player is put in a situation where they have to choose one of those nine categories in order to create their character. Depending on the answer, however, they have to “roleplay” the character as such. For instance, if a player chooses to play a CE cleric (one of the many classes in D&D), that would mean that they would believe in no deity, which is fundamental for a healer, since they pray to their deity in order to gain powers and heal their allies, be selfish, and doing the exact opposite things of what a cleric is supposed to do and act like. The same implies to the character’s decisions and moral barriers. For example, the DM has put the CE rogue (the assassin of D&D) into a moral dilemma: to sacrifice themselves so the rest of the party can live, or sacrifice the party so the Rogue can survive a ferocious battle. For a CE rogue, the answer would be simple — to sacrifice the party. But for a CG rogue, the player would have to make a decision according to the character’s morals, beliefs, and viewpoints on various — and specific — topics.

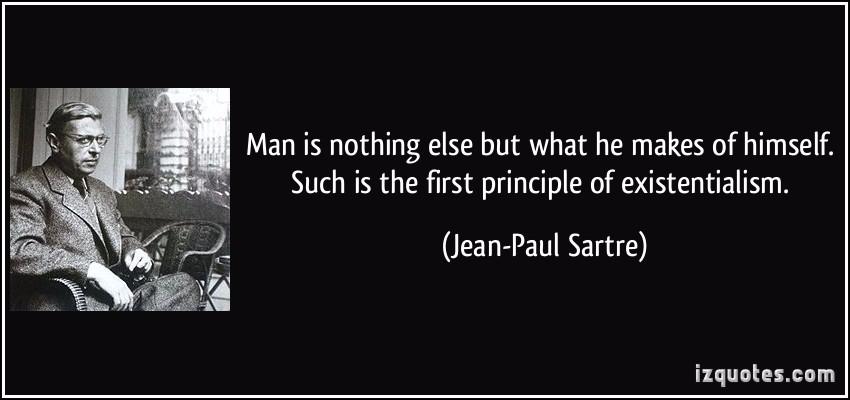

Existentialism and D&D: When philosophy meets D&D

In conclusion, each character can act however they desire because they choose to act like that. They have the freedom to act however they please, always according to the character’s alignment. Nonetheless, we should keep in mind that everything can change. If a player frequently undertakes certain sorts of surprising behaviors, for example, the DM will reassign your alignment, which is your character’s ethical and moral stance. If you are intended to be LG but continuously disobey the laws, you can end up becoming NG. We are created by our repeated acts, according to Aristotle: “We are what we repeatedly do”. We become the devil if we perform wicked things in life. We may become sages by reading literature. We become the priest if we are nice and polite. From this perspective, our lives are not finished paintings or books; rather, we dab the canvas or write our tale with each deed.

References

- Alignment, dungeonsdragons.fandom.com, Available here

- Dungeons & Dragons, britannica.com, Available here

- Dungeons & Dragons, wikipedia.org, Available here

- Moral Philosophy and the Alignment System | Philosophy in D&D | The Innkeeper, youtube.com, Available for watching here

- Teaching Ethics with Dungeons & Dragons, blog.apaonline.org, Available here

- Christopher Robichaud, Dungeons and Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom Checks, Series edited by William Irwin, published by John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2014