By Socratis Santik Oglou,

Bonnie and Clyde (1967) consists of a milestone in the history of American cinematography, as many film lovers may already know. It is cruel, filled with anarchy, comedy, and romanticism, as it is also heartbreaking and astonishingly beautiful — story plot-wise — at the same time.

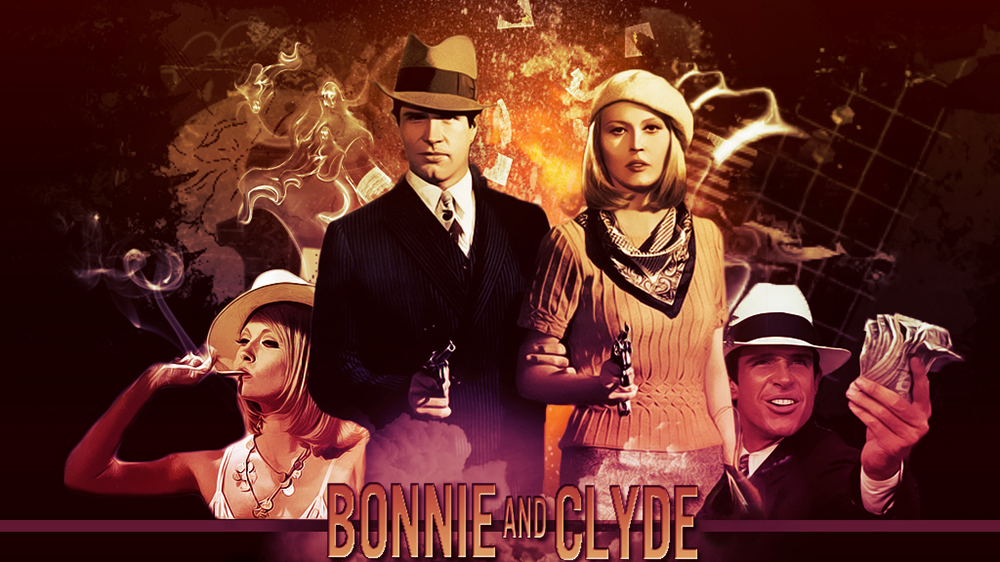

The film is a two-way gangster movie that depicts the same time comedy, horror, romance, and violence. The film’s producer is the well-known Warner Bros. Pictures. Warren Beatty, who is the lead male figure in the film, plays Clyde Barrow, while Faye Dunaway plays the role of Bonnie Parker. The film’s script is written by David Newman and Robert Benton and it is based on historical elements from the lives of the two misfits who became romantic fugitives and folk heroes. It is a composite portrait of numerous illegals around the turn of the century. The most “adrenaline-boosting” events are accompanied by classic banjo music.

Although set in 1930s countryside America, Bonnie and Clyde contains several themes that consist of key characteristics of the 60s’ youth period (i.e. the rebellion, the fight against discrimination, and the fight against the American system). It is also characterized by the values of that time, like the anti-hero protagonists with the strict society that surrounds them, the references to sexual conflicts, all the psychological problems that may come with relationships, and the unhappy-ending trend that dominated in the cinemas at that time.

To talk about the visuals of the film, we see plenty of use of unique cinematic effects, as well as the juxtaposition of comedic and serious elements. The director makes use of slow and fast motion, ironic counterpoint of sound and image, and stylized images of memory and sequencing of dreams. Like most of Arthur Penn’s films, Bonnie and Clyde still has a loosely organized visual plot that brakes for the traditional Hollywood dramaturgy standards.

The film belongs to the category of “Art films,” in which the American film industry aimed to appeal to a small but vocal set of moviegoers, which includes not only Americans but also cinematographers. Films like this reflected the audience’s sexual and societal beliefs around these years. In fact, Bonnie and Clyde may be the first film to fully articulate the values of this new cinematic era. If you watch the movie, you will feel like you have seen something like this before, exactly because this particular movie is an important milestone in filmography, which has a clear effect on postnatal movies.

We see Bonnie and Clyde using cars as their means of transportation to cross the American countryside while living freely. This is a contradicting element to the film’s “anarchist” vibe because the couple uses cars and spends money, while their fellow citizens, who are “slaves” of the system, struggle to find food and freedom in that chaos. The film also displays a contrast between the past and the present, the big city life and the countryside; sorting that we actually see in this era’s filmography.

These two illegal primitives are after avaricious bankers and the police officers who protect them; in other words, “the system”. The two primitives exude the dominant air of the 60s’, era of anarchy and liberation. The heroes are doomed halfway through the film, but nothing whatsoever could prepare any viewer for the apocalyptic horror of the film’s unhappy ending. I find Penn’s way of directing very interesting, because, in this infamous ending scene, Bonnie and Clyde are not just killed. In fact, we see their bodies fall apart while being ripped open from multiple viewing angles, in this complex, dramatic montage.

The film’s ending brutality is as groundbreaking for its day as difficult to comprehend nowadays. The film’s conclusion consists of an important, for its days’ film industry at least, innovation that contracts all the clichés. Although I think that this film is fairly important, because it depicts for the first time in American cinema that the human body is made out of flesh and blood, while underlying the ugly and sometimes unfairly done consequences of human brutality and gun violence.

Penn and Peckinpah disrupted a decade-long noble cinema tradition, that death is only a state of forever sleep, by presenting what all-powerful current armament can do to the human body, bringing the American film closer to reality. To conclude, in my opinion, the classic western aesthetic, combined with the gangster theme, makes this movie an important inclusion for film lovers.

References

- Lester D. Friedman, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, Cambridge Film Handbooks, Great Britain, Cambridge University Press, 2000, assets.cambridge.org, Available here

- Bonnie and Clyde’s “Other Side”: The Good-Bad Outlaws of Larry Buchanan, asjournal.org, Available here

- David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson, Film History: An Introduction, McGraw-Hill Education, 2nd edition, 2002