By Angeliki Georgakopoulou,

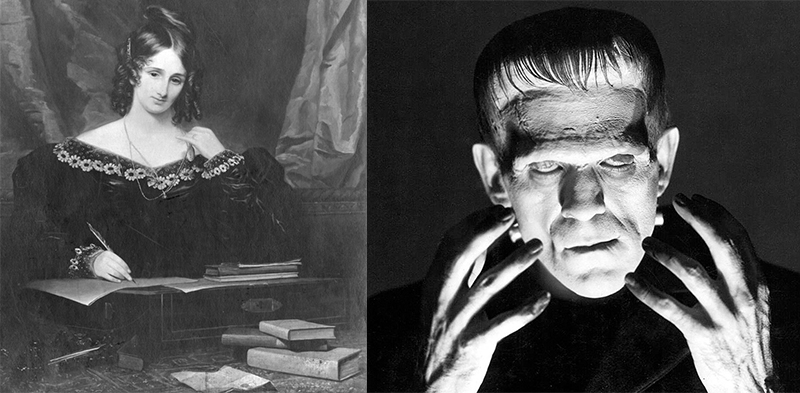

Espoused within the embryonic pedagogy of differing contexts, worlds of upheaval act as an overt framework, through which the motivation for acceptance functions as a catalyst for the examination of the complexity of individual and collective lives. The construction of such cosmoses allows composers to critically comment on the conflicts presented by the status quo, eliciting ideological progress, and societal transformation. The textual analysis of Mary Shelley’s romantic phenomenon Frankenstein (1818) and Fritz Lang’s eco-critical commentary on the Weimar Republic, through the silent film Metropolis (1927), positions them as epic parables against the scientific paradigms of the enlightenment and modernist society. Subsequently, through the vastly divergent literary constructs and the mimetic and diegetic elements employed, the composers provoke thought for the purpose of eliciting shifts to lucidly capture humanity’s inherent thirst for belonging.

In the constructed calamitous cosmos of Frankenstein, the interplay between rationalism and emotionalism underpins Shelley’s critical reasoning to warn against injustice and scientific progress through her vivid characterization. The epistolary form of the novel renders greater realism to the diegesis of this social and political world. In this hybrid text, Shelley comments on the dichotomy between “benevolence” and “monstrosity” by shaping Victor’s pursuit of solace through an idyllic romantic lens. Intertextual references to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem align with the world’s aesthetic gothic design in the ethereal setting between life and death in the “lands of mist and snow” in the Arctic.

The didactic nature of Frankenstein allows for an insight into Shelley’s commentary on the concepts of William Godwin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for the purpose of warning against the lack of solace and the scientific paradigms of the enlightenment. The “creature’s” longing to “join” an egalitarian society and system of politics prompts his observation of the impact of human companionship, as represented within the utopianism of the DeLacey family. Alternatively, the subversion of the allusion to Paradise Lost (1667) by John Milton, “But how was I terrified, when I viewed myself in a transparent pool!” introduces the theme of verisimilitude, which contravenes prevailing contextual attitudes regarding appearance, and elucidates the monster’s personal world of “pandemonium”.

In addition, Shelley’s critique of societal inequalities, stemming from her influence by her familial and social milieu, is manifested through the paradoxical representation of knowledge and innovation. The personification of the thunder that “bursts with a frightful loudness” augments the mimesis of this romantic world and constructs a reflection of Victor’s dark and morbid psychological torment in his private world.

Comparatively, the indirect pursuit of solace, through one’s motivation to restore order and justice is explored in Frankenstein, within the scope of aspirations and predicaments. The description of the “creature” as a “fiend” holds an epistemological function in delineating the upheaval that derives from the unjust and unethical creation through galvanism. Thus, the invocation of Michelangelo’s painting represents Victor’s illusion of parental responsibility, as well as Shelley’s criticism of society’s superficiality and the necessity of the restoration of classical ideals through romanticism.

In her postmodern literary criticism, Molly Dwyer, through a historicist lens, perceives the “creature” as an allegory for the calamitous outcomes of the French Revolution, transpiring its character into a plethora of apocalyptic warnings. In this way, Shelley further comments on the negative ramifications of imperialism and colonialism. The multiplicity of ideas stemming from the human motivation to gain a sense of solace, provides an insight into Shelley’s romantic response to contextual concerns, within her socio-politically constructed world.

The romantic idealism conjured in Frankenstein is starkly contrasted with Lang’s Marxist criticism of modernist industrialization for the purpose of driving political action. In Metropolis, the romanticized extended metaphor of the mediator representing the philosophy of unity and solace, as introduced in the epigraph, creates a cyclic structure that is deepened through the religious overtones in the alternating shots between the chiaroscuro effect on Freder’s expressionist reactions and the Moloch allegory. In this scene, through the allusion to the “Old Testament pagan God, Moloch”, according to Kruse, Lang fuses the pagan past with the capitalist present, emphasizing the continuity of dehumanization and despotic tyranny, hence commenting on Freder’s motivation to achieve a state of solace for himself and the workers.

This idea is further explored in the catacombs, whereby solace derives from political conversion, which translates to a religious calling. Thus, the long shot of the workers bowing down to the messianic figure of Maria, positions her as a beacon of hope and solace, hence shaping the catacombs as a historically accepted medium of consolation in periods of upheaval.

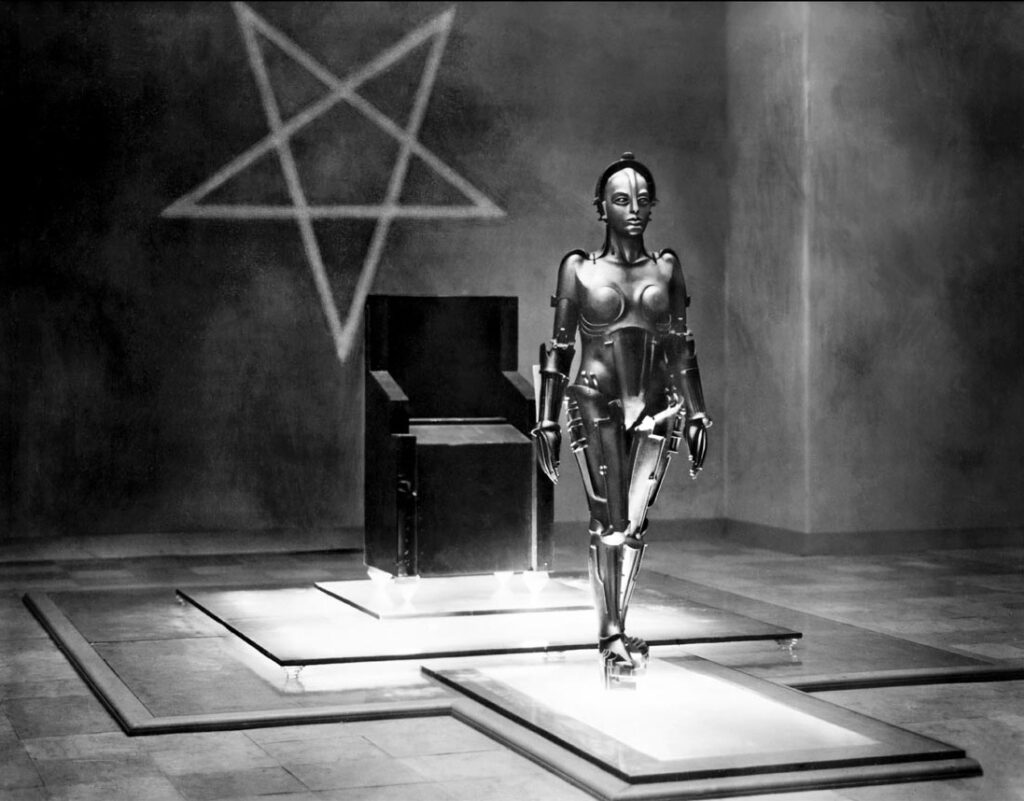

Moreover, in Metropolis, Lang’s manipulation of the silent film form allows him to comment on the upheaval, which stems from the recurring dystopic trope. Through the representation of the Cyborg, Lang condemns capitalist greed, as the paradoxical interdependency between man and machines constitutes the obverse of solace and equality.

This notion is further illuminated through the religious symbolism of the Cyborg’s costume “Whore of Babylon”, which traditionally foreshadows the apocalyptic destruction of utopia. However, Lang, similarly to Shelley, subverts the biblical reference through the metanarrative form of the scene to critically reinterpret the notion of scientific endeavor and economic growth as “the weapons of demagogues”, as reiterated by Roger Ebert, as well as to criticize the patriarchal construction of femininity, which focuses on the representation of women as “Madonnas or whores”.

To some extent, Metropolis ornately demonstrates Freder’s aspiration to seek justice for his “brothers”. The interchanging shots between Freder and Fredersen, as the former reveals his ambition to share the light of the city with the workers, position Fredersen as the emblem of capitalist insensitivity, hence epitomizing the lack of solace and justice within periods of consumerist dominance.

On the other hand, the mid shots of Maria bathed in light represent her as a “Saint-like figure”, as her sermon on the Tower of Babel echoes the Bible by intensifying the ambiance of suspense and functioning as a prolepsis for the restoration of order. Therefore, Lang’s film appeals to the notion of solace explored in the text by Shelley, yet uniquely reinterprets the world through the framework of feminism and surrealism.

In summation, during periods of upheaval, individuals and communities are considerably motivated by the need to gain solace and unity. However, through the dynamic diegetic representation of social and political worlds, which mimic reality, it is evident that humanity is simultaneously driven by the desire to restore order and justice by enthusing change. Thus, through the composition of literary cosmoses, which respond to upheaval and challenge contextual and literary conventions and forms, authors trace the notion of solace and evoke self-reflection.

References

- “Metropolis”, rogerebert.com, Available here

- “Frankenstein By Mary Shelley”, vcestudyguides.com, Available here

- Kashmala Haidar, Frankenstein and Worlds of Upheaval, studocu.com, Available here

- “The Strange and Twisted Life of Frankenstein“, newyorker.com, Available here