By Katerina Dimarogkona,

“Things may come to those who wait, but only the things left by those who hustle”.

— Abraham Lincoln

In Kenya, tribes in desperate need of water have developed highly sophisticated rituals, that try to predict and control the rain. This art of rainmaking helps them give a sense of control against the unpredictable, even though the practices are essentially superstitious. Perhaps in a similar way, one can see the spread of strange ritualistic behaviors in a new productivity-obsessed community, which is buying books, joining various programs, attending seminars, and drinking protein smoothies and “magic potions” to work harder, in order to optimize success. It is an ethos that has permeated mainstream culture, which has become a hardly questioned virtue. The self-improvement industry was worth $9.9 billion in 2016, and it is expected to grow to $13.6 billion in 2022 (UTA, 2019). Consciously or not, we feel this pressure not to fall behind, to become more than what we are now. However, it is entirely unclear whether this self-help practice is working. And more importantly, do we want what it promises?

Self-help can be somewhat of a scam for many reasons. First, people who promote self-help products and whatnot try to convince other people that it is an ever-continuing process, a “self-help journey”, in which, in order to continue, the consumer needs to buy a constant supply of productivity material. It is easy to gain a false sense of accomplishment by just reading these books. Many people fall into a trap where they feel addicted to consuming such material, without ever applying it to their own life. In the long term, many of the changes they make have no impact on their lives, making all that money and time spent wasted. There is also a second, more interesting category of people who seek self-help, and that is people who have no intention of engaging with the material at all. “Self-help porn” is a term that describes the behavior of people who procrastinate, watch self-help vlogs while binge buying exercise programs, and so on; just to bury the guilt and escape in the illusory hope of getting better or just to fantasize about what it would be to solve their problems. The other problem about it is the suspicious credentials of supposed “gurus” who sell miracle cures that will “change” people’s lives, while they themselves are successful only as authors of these books and not in a real-world context.

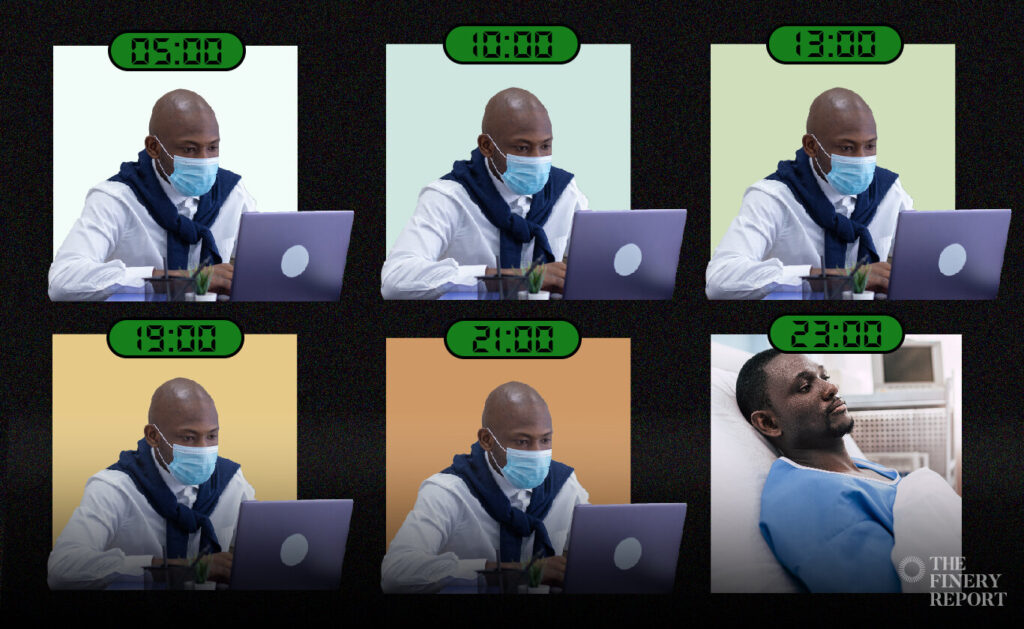

The deeper problem, however, is not the doubtful efficacy of productivity self-help, but the toxic culture that surrounds it. This so-called “hustle culture” is based on a mindset of continual growth, which is predicated on working harder than those around you, to be in the top 1% of productive employees. It paints a picture of a dog-eat-dog world, where success is everything, and work is all-consuming. The effects of such a lifestyle are obviously destructive for mental health, as they create this anxiety of never doing enough, continually pushing yourself — essentially being your own domineering boss. At its root, what productivity self-help ends up doing is putting a little technocrat in your head, creating a perfectly efficient machine of the self. It neglects natural ways of behavior to make a person their own slave. But if you are your own slave, who is this other self that you are serving?

Self-help culture also propagates that you should dream big, make your mark in the world, and that with hard work dreams are achievable. It believes in this notion that everyone is exceptional at something and it kind of looks down on someone who does not have a grand career goal in mind. It sees a meritocracy that rewards, albeit not easily, hard work and ingenuity. So all those who are worthy will eventually be rewarded.

But we can spot a contradiction here. And that is that, if we all believe we are exceptional, we believe we can get exceptional things. Focus on the word “exception”. By definition, it refers to something that happens very rarely against a generally true rule. So, we both expect to be exceptional, and also believe that anyone who tries succeeds. Not everyone can be in the top 1% of productive people. That is just not how maths works. Then, it is also based on the belief that we all have to make a mark on the world, to influence it deeply, to be a Napoleon or an Einstein, or else we do not matter. The way this works in action is that we both try to work harder than others to surpass them, because we understand that there are not enough dream jobs for everybody, and simultaneously judge people when they are not chasing some grandiose dream. Just being a passive employee, whose life does not revolve around work and success, is frowned upon. We can sadly see this effect on a cultural level.

We live in this weird time, where companies expect us to be enthusiastic about what we do, and you see that in ads. They always ask for a store manager who is passionate, does extra training programs in his free time, and has dreamed about being a store manager since they were a child. We are cruelly asked not only to be overworked but to also be happy about it. And this unrealistic expectation that all work should be a dream job is just absurd. This weight falls on our shoulders, as we begin to feel a deep dissatisfaction with our lives. We are told that having dreams is essential, that those dreams can be realized, that our potential is infinite, etc, and all this process does is leave us always yearning for more productivity, or else we are lazy.

Billionaire entrepreneurs are the inspiration for this trend, who make it seem like, if you have the work ethic of a CEO, you can essentially become one. On a psychological level, young people today are told that they could have aspirations of becoming rich and influential, and this productivity obsession might be a way of closing the great divide between what our culture has told us we can achieve and the bitter reality of the jobs we can actually get. More pragmatically though, it is a way to control our fate against a precarious job market. Our society is characterized by great instability and change, a fact which is contributing to young people’s work anxiety. The so-called “precariat” are people who face an unstable future working in a gig economy, in a society where future job market trends are unknown, and almost no degree or qualification is beyond becoming outdated.

My take on why this happens is partly that we are trying to make a necessity, having to exert great amounts of effort to compete in the job market, into a virtue. We should try to become better people, but define what is better for ourselves. If you give up your sleep, your relationships, and your free time, it is not clear how you are virtuous and not a workaholic.

References

- The Self-Improvement Industry Is Estimated to Grow to $13.2 billion by 2022, brandminds.live, Available here

- The rise of hustle culture: why millennials have become obsessed with work, inspiringinterns.com, Available here

- From productivity porn to mindful productivity, nesslabs.com, Available here