By Katerina Dimarogkona,

Public education was created to free people’s minds from narrow-mindedness; to teach students critical thinking, foster creativity, and knowledge that will help them find a job; to ensure that voters have sufficient knowledge to defend democratic regimes against the ever-present threat of tyranny. Or so we keep hearing. The actual history of its adoption on a global scale is darker and less about the propagation of enlightenment values than is usually assumed.

In the midst of the Napoleonic wars, Prussia found itself bitterly defeated. In the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt (1806), the previously unchallenged great power lost half of its territory, partly because of Napoleon’s strategic genius. Yet, it was also thought to have been caused by the lack of organization in Prussian affairs. The army was unruly and the soldiers were acting for themselves. The administration was unable to successfully tend to the task of war. So, as a reaction to those criticisms, efforts were made to modernize the administration, commonly referred to as the Prussian Reforms. The goal was to strengthen the economy in order to make tribute payments to France and restore the power of Prussia by uniting it. More importantly though, the powerful feared that something like the French Revolution was coming their way. All the sleeping forces were re-awakened, the misery and weakness, the old prejudices, and the shortcomings were destroyed.

The point was that monarchical absolutism had to go. Enlightenment ideas were so popular, that violent revolution was highly probable. And this fear of the overthrow of the “ancien regime” led to the espousal of the principles of the French Revolution by policymakers. There would be a “revolution from above”, meaning that some concessions would be made to revolutionary demands, so that power would not be lost, and that social upheaval would be avoided.

These principles’ power is so great – they are so generally-recognized and accepted, that the state that does not accept them and must expect to be ruined or to be forced to accept them; even the rapacity of Napoleon and his most-favored aides are submitted to this power and will remain so against their will. One cannot deny that, despite the iron despotism with which he governs, he nevertheless follows these principles widely in their essential features; at least he is forced to make a show of obeying them.

That fear, as well as the wish to revivify the class system in Prussia (nobility, bourgeoisie, peasantry), informed the creation of the Prussian school system, the father of most school systems in Europe and the US today. It is largely attributed to Wilhelm von Humboldt among others. Humboldt was in favor of the enlightenment ideas and wished to create a system where all would have a chance at personal growth through the school system, an idea he called “Bildung” (education, formation in German).

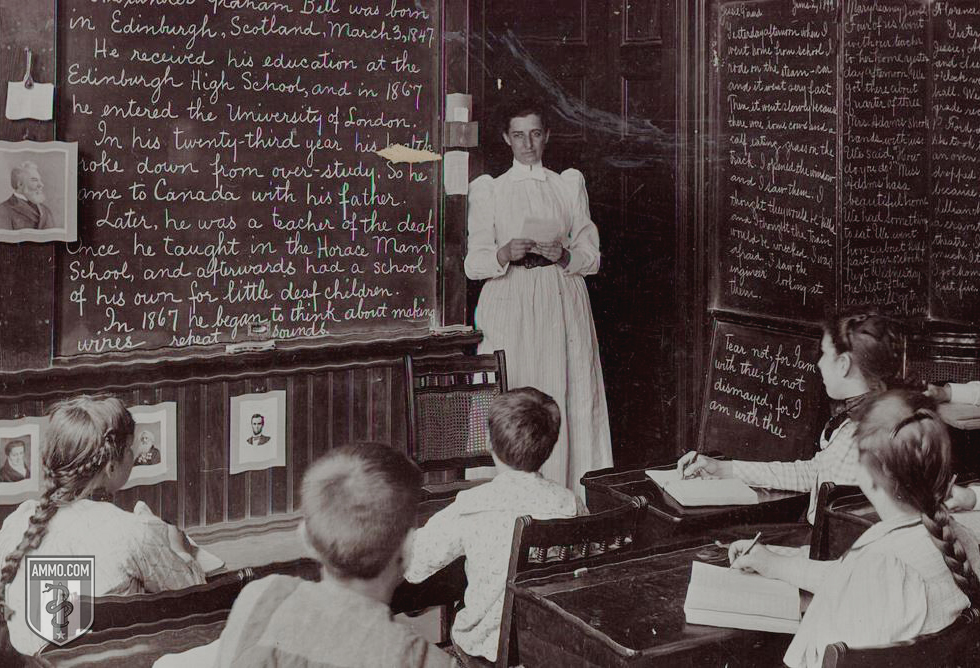

However, education for peasants was based more on discipline, subservience, conformity, grading, mindless memorization, suppression of creativity, suppression of intelligence, and other negative aspects of modern schooling. It consisted of an 8-year program of compulsory education for everyone (Volksschule), a school that prepared the student for critical thinking, which is required in scientific pursuits (Realschule), and the Gymnasium, which was a preparation for university. It should be noted that peasants had access only to Volksschule. Another central part of the curriculum was the effort to create a common national identity, in order to promote harmony and adherence to the rules of the existing social order.

The system was largely successful in reducing illiteracy and in strengthening state power, leading various European rulers to adopt it. As a result, compulsory school systems have been linked with the rise of the nation-state and are largely thought to be one of the reasons for its success. From there, it was adopted in the US by academics who studied in Prussia and came back to staff most of the universities. This system also made sense in the age of industrialization, as there is no personalization in it. It smoothes out differences between people, thus eliminating a lot of societal conflicts. And the reason it was adopted had probably more to do with these factors rather than with some abstract concern about the human spirit on the part of policymakers.

“So what if in the age of smartphones our school system comes from an agrarian monarchical society in the mid-1800s?”, you might ask. Indeed, many endure school and happily forget about it later. It is acceptable to just bear the education process, make friends and memories, and learn useful knowledge of your own volition later in life. Modern science disagrees with that notion, though. Children are formed in unconscious ways by their experience in school. The learning methods used today are outdated and unnatural as well. All alternative education practices use exploration and play as tools to help the learning process instead of memorization and testing that kill curiosity and creativity. As a professor of biopsychology, Peter Gray, puts it: “The biggest, most enduring lesson of school is that learning is work to be avoided when possible.”, or even Albert Einstein: “One had to cram all this stuff into one’s mind for the examination, whether one liked it or not. This coercion had such a deterring effect on me that, after I had passed the final examination, I found the consideration of any scientific problems distasteful for an entire year.”.

This will not do. Our educational system in effect kills our prospect for developing our natural talents, maybe not completely, certainly though doing a lot of damage. It is bizarre how in our society we claim to value education so highly, as a pillar of democracy, of self-growth, as a solution to all societal ills, and yet make no specific demands to our governments concerning our education. As far as I can tell, there is no mass grass-roots education activist movement. Maybe those in power have no interest in instating truly valuable education reform. Maybe it is time we started discussing collectively what reform might be suitable to bring our educational systems to this century, to serve us, the people being educated.

References

- Aditi Pai, Free to learn: Why unleashing the instinct to play will make our children happier, more self-reliant, and better students for life, in Evolution: Education and Outreach, vol. 9, 2016, researchgate.net, Available here

- How to Break Free of Our 19th-Century Factory-Model Education System, theatlantic.com, Available here

- Christopher Clark, Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947, Ch. 7, 2008

- Karl-Ernst Jeismann, American observations concerning the Prussian educational system in the nineteenth century, in Henry Geitz and Jürgen Heideking, eds. German influences on education in the United States to 1917, 2006, pg. 21–41

- Kerry J. Kennedy, Citizenship, Education and the Modern State, Psychology Press, 1997

- Walter Demel, Uwe Puschner, Deutsche Geschichte in Quellen und Darstellung, inVon der Französischen Revolution bis zum Wiener Kongreß 1789–1815, Reclam Verlag, 1995, pg. 88-91

- Albert Einstein, Stephen W. Hawking, A Stubbornly Persistent Illusion: The Essential Scientific Works of Albert Einstein, Running Press, 2007, pg. 346