By Angeliki Georgakopoulou,

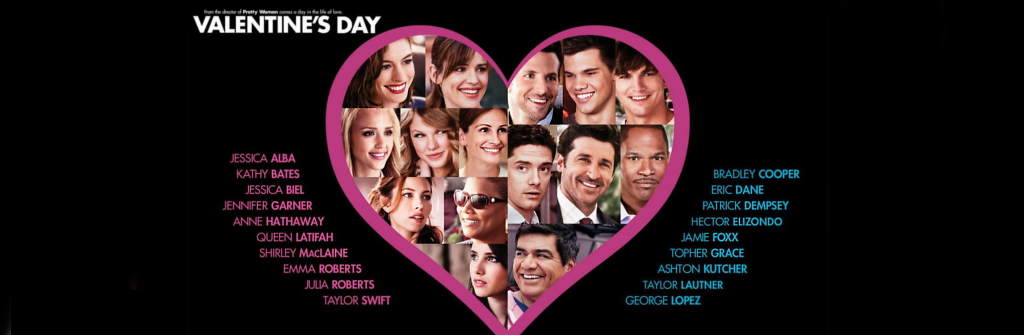

The classic 2010 romantic-comedy film Valentine’s Day has been a February favorite for the last decade, with reviewers claiming it as “a pleasant, undemanding movie”, espousing the elation of being in love. However, as one takes a more critical dive into the plot and character relationships, this “mask of love” melts into a poorly fabricated attempt at reaching and relating to mass audiences.

As the movie begins, the audience is immersed in the overload of clichés that burden the plot. The structure of the film follows a myriad of couples and additional characters that develop and unfold against the backdrop of Valentine’s Day, with several typical formulas employed in their exploration and construction; the “best friends” trope, the plight of unrequited love, the cheater, the misunderstanding, and the innocent teacher-student crush, to name a few. However, this attempt at producing a “one movie fits all” lacks substantially in the field of creating intimate connections between characters and audience. Quite frankly, the audience is not given the opportunity to care enough, as the main characters — although possessing potential — never fully mature into three-dimensional personas.

Nonetheless, caught up between the “over-the-top” romantic gestures and the stereotypical melancholy of singles on Valentine’s Day — as encompassed primarily through the role of Kara Monahan, who indulges in candy to soothe her loneliness — comes the voice of cynicism in the character of Kelvin Moore. Kelvin, a sports presenter on television, states that Valentine’s Day “gives me acid reflux… We spend a lot of money, nobody cares, it is not even a real holiday. We do not take the day off…”. And somewhere there lies the truth of Valentine’s Day… As consumers we have fully volunteered to participate in the grand scam of “love”. Valentine’s Day becomes a yearly competition of flexing the most luxurious gifts, instead of adhering to its traditional role as a celebration of what truly unites individuals — unconditional love.

Moreover, the movie’s focus on bodily hedonism — as the film ends with the words “Let us get naked” — further deviates from and devalues the central purpose and meaning of Valentine’s Day, as it simplifies it to the common denominator of sex. This inaccurate equation of sex with love is misleading to the audience, as it creates the false pretense that love and intimacy are only expressed through physical contact.

Historically speaking, however, there are numerous Catholic legends surrounding the origin and development of Valentine’s Day. One such legend involves the story of Valentine, a priest who served during the third century in Rome and fervently believed in the value of love. Upon Emperor Claudius II’s decision that single men performed more efficiently in battle than those with wives and families, he banned marriage for young men. Valentine, realizing the injustice of the command, defied Claudius and continued to perform marriages for young lovers in secret. Once the emperor discovered Valentine’s actions, however, he ordered that the latter be put to death. As such, February 14th acts as a remembrance and panegyric of the power, value, and strength of love in all its forms — familial, platonic, and romantic.

Overall, although the film Valentine’s Day draws on “innocent” stereotypes with a sprinkle of comedy, to appeal to the average person relishing their popcorn whilst sitting on their couch, there are some underlying issues that come to the surface when analyzing the values and messages that this movie is conveying in relation to Valentine’s Day.

References

- History of Valentine’s Day, history.com, Available here