By Timoleon Palaiologos,

The once-mighty British Empire used to cover more than 20% of the world’s entire land surface. It was an empire that the sun never set on, as there would always be a place in the globe where it would still shine. And so, it would be fair to say that the British army has been almost everywhere in the world.

In the 19th century, the Empire still stood strong and had interests in southern Africa, where the British cape colony already existed since the early 1800s. The existence of Europeans in South Africa had already been perennial since the Dutch first formed a colony in the area in the mid-1700s and their descendants, the Boers, remained and formed their own colonial states. The British Empire had already enacted the British North America Act of 1867, practically forming the dominion of Canada, and it was believed that a similar situation could develop in South Africa with the Indigenous Kingdoms and the Boer states. For that specific reason, Sir Bartle Frere was appointed High Commissioner of South Africa for the British Empire, with his main objective being the achievement of said similar agreement in South Africa. The major antagonizers were considered to be the armed Boer South African Republic and the indigenous, also armed, Kingdom of Zulu. Frere, in an attempt to provoke war and force the Zulus into an uneven battle, sent an ultimatum on the 11th of December 1878 to King Cetshwayo kaMpande of the Zulus with terms impossible to accept. King Cetshwayo did not respond to the initial ultimatum and an extension of the ultimatum was granted until January the 11th 1879, but the Zulu King still did not answer.

Battle of Isandlwana

With no answer to the ultimatum, Frere, without the consent of the British government, ordered Lieutenant General Frederic Thesiger, second Baron Chelmsford to invade Zululand on the 11th of January 1879, marking the beginning of the Anglo-Zulu War. The first major armed engagement that occurred during the war was the battle of Isandlwana. On the 22nd of January, the British army consisting of approximately 1,800 men, some of which were native Africans and colonial settlers, came against a Zulu army of approximately 20,000 Zulu warriors under the command of Ntshingwayo Khoza. Earlier that morning, Chelmsford, thinking that his scouts had found the main Zulu army, split his forces in half, taking 3,000 soldiers with him in an attempt to pursue the enemy and force them into battle, leaving only 1,800 men in the encampment in Isandlwana. However, the British General was tricked by the Zulu that had wanted to mislead the British and had outmaneuvered Chelmsford and his forces and now had the opportunity to attack a vastly inferior number of enemies. Even though the technological advantage of the British was overwhelming (the Zulus’ main attack weapon was the traditional “assegai” spears whilst the British’ were using guns), the greater numbers of the Zulus, in the end, decided the outcome of the battle. The British suffered as high as 1,300 casualties, while the Zulu is estimated to have lost twice as much.

Battle of Rorke’s Drift

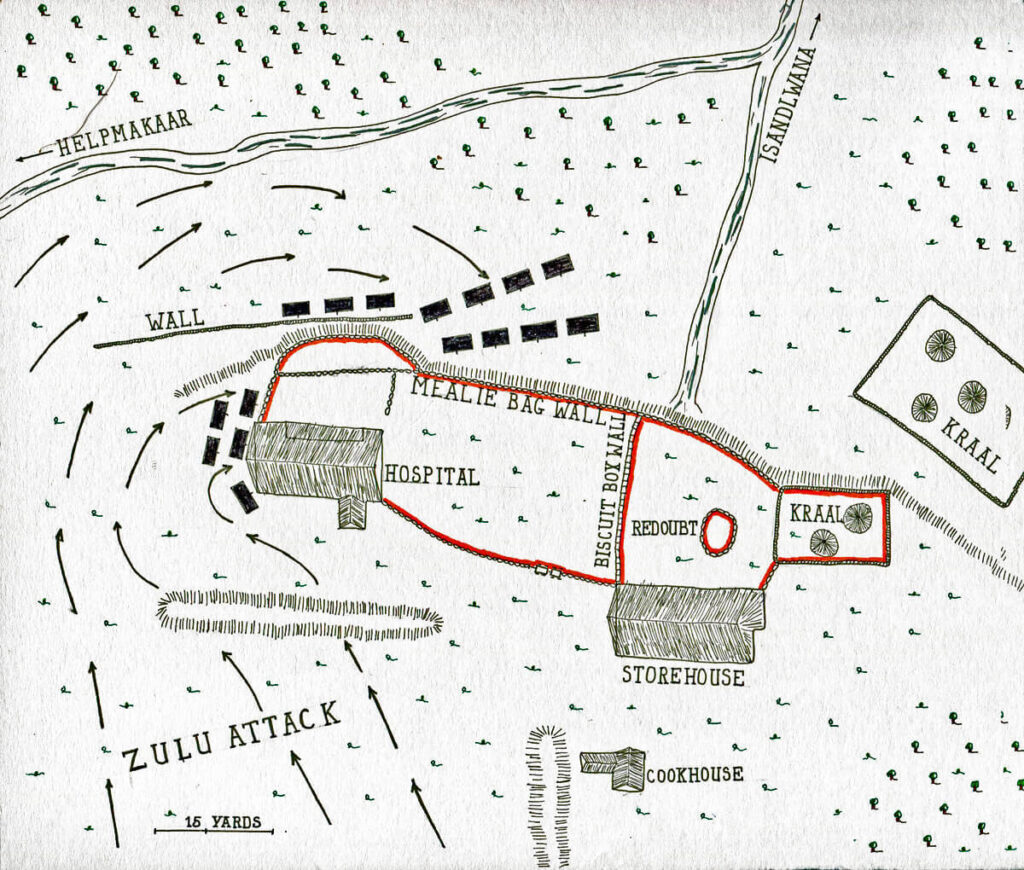

With the defeat of the British army in Isandlwana, a detachment of Zulus began to march against the British encampment in Rorke’s Drift. The British were stationed in a mission station of the Church of Sweden, numbering roughly 400 men under the command of Lieutenant John Chard. They were informed of the tragic defeat in Isandlwana and the enemy’s movement towards their position and began to prepare their defenses. They fortified the storehouse and the hospital, making a defensive perimeter with mealie bags expecting to take cover behind them. Preparing for the battle, the British already knew that they would be encircled and outnumbered by a larger army. The Zulu reserves of Isandlwana that would arrive on the afternoon of the 22nd of January walked 32 km in a few hours just to enthusiastically attack the British outpost and overwhelm their positions. Lieutenant Chard had correctly calculated that the forced march of the Zulu army would have resulted in excessive fatigue for the soldiers and that would have an impact on their fighting abilities. The British also enjoyed a technological advantage as the Zulu warriors used short spears and shields as their main weapons. At the dawn of the battle, and when the British saw the enemy army of approximately 3,000-4,000 strong Zulu under the command of Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande, 100 men of the Natal Native horse troops fled the field of battle to Helpmekaar. Seeing their fellow soldiers leaving, another company under Captain Stevenson retreated reducing the number of the defenders to 150.

The initial Zulu attack was aimed towards the north wall where the defenders had fixed bayonets involved in a bloody hand-to-hand combat scenario. Constant attacks by the Zulus forced the British troops back inside the hospital, completely abandoning the defense of the north wall. Slowly but steady the overwhelming Zulu attacks forced the Brits to abandon the Hospital as well resorting to a final stand within the storehouse barricades. The repeated attacks continued until approximately midnight when the Zulus began using intimidation tactics against their enemies. The situation on the British side was somewhat desperate. The ammunition was running dangerously low — of the 20,000 rounds only around 900 rounds were left — and the remaining soldiers were exhausted after 10 hours of continuous hand-to-hand combat.

The following day at around 08:00, the relief force of Lord Chelmsford approached the British position in the station signaling the heroic victory of a few British soldiers against a vastly superior enemy. The aftermath of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift saw 17 British soldiers killed in action in contrast to approximately 350 Zulus. However, the number of the Zulu casualties varies and it could be anywhere between 350 to approximately 1,000 killed during the battle and in captivity as retaliation for the British loss in Isandlwana.

References

- Battle of Rorke’s Drift, britishbattles.com, Available here

- Battles of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift, britannica.com, Available here

- The Battle of Rorke’s Drift, militaria-history.co.uk, Available here