By Katya Mavrelli,

The paradigmatic shift of U.S. foreign policy away from the Middle East exemplifies a new world order that has come to dominate the international political sphere. Old regimes are changing, previously central players are taking an active step back from the spotlight of international relations, and new powers are defending their place at the table. And amid all this seemingly chaotic process, China is trying to carve its own place among other leading actors. But how have Chinese foreign policy priorities been translated into policies when it comes to different regions of the world?

The more the thirst of the Chinese government for greater influence and more economic growth grows, and the more the desire to carve a more central role in the internal sphere is not quenched, the more the foreign policy decisions are oriented towards this direction. Over the past years, China has tried to form ties with individual countries rather than with the region as a whole — the more personalized approach to foreign policy is what sets China apart from other nations. And while it is seeking very different things from each of these nations, the preservation of regional interests lies at the core of these interactions.

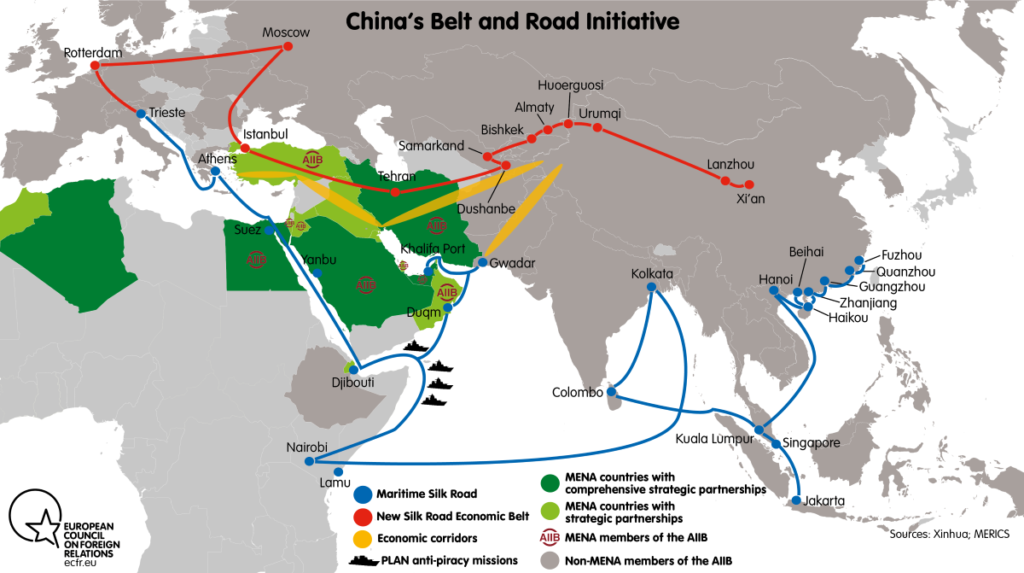

As China’s influence grows and as it seeks new tools with which it can satisfy its needs, it has no other option, but to turn to the Middle East. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is the one that moves the world’s resources, determines foreign policy initiatives, and sets a course of action for national agendas. It is in the epicenter of all national agendas, for the simplest reason that any development in the region has echoed across the international sphere. The Chinese approach has not been designed in a “copy & paste” manner, which would imply that it would be implemented in the same way for all regions and states that China is interested in. On the contrary, the strategic approach of the Chinese government is determined by the capabilities, necessities, and potential of the region that is under the microscope. When it comes to the MENA, therefore, the possibilities are endless.

China’s partners in the MENA are not limited to the oil kings, namely Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, but also include states like Israel, Egypt, and Iran. Despite the peculiar combination of regional players and the very diverse interests that are at play, when it comes to Chinese investments, there is a certain homogeneity in their approaches.

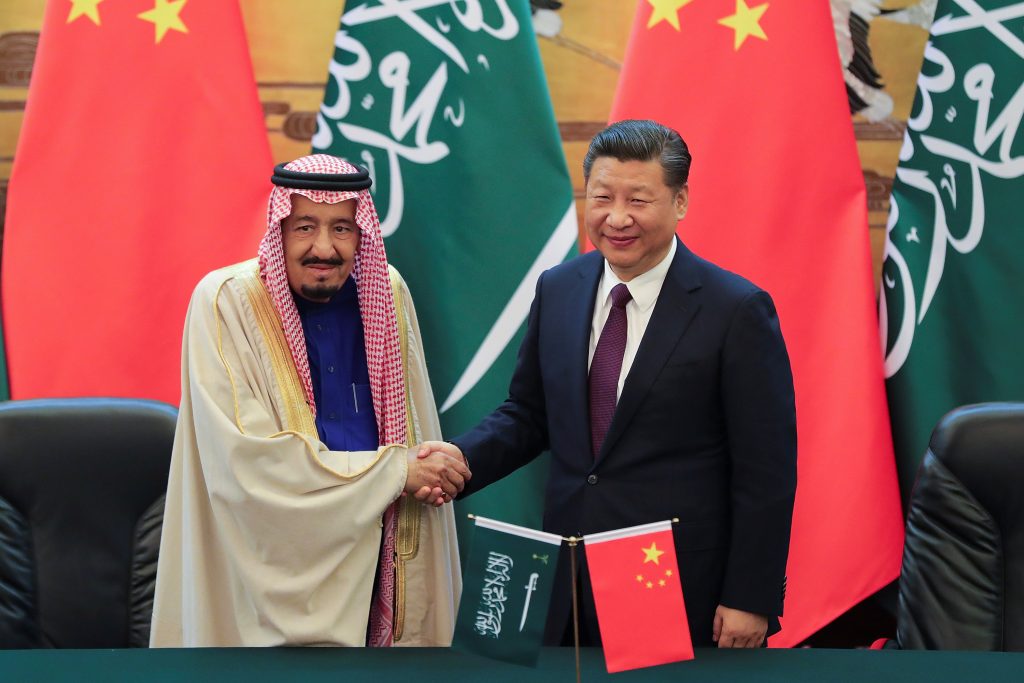

The Saudis are the most important and largest trading partners in West Asia and Beijing is the Kingdom’s largest trading partner worldwide. Many would question the extent to which this strategic interaction is anything more than a consensual symbiosis on the energy market — and the international arena in general. But upon closer examination, one can see that their ties run deeper than simple superficial relations. Chinese construction firms have acquired a dominant role in the Kingdom’s economy and have helped the Saudis to develop better infrastructure, while Riyadh has been particularly interested in developing oil refineries and petrochemical production facilities in China, the performance of which is optimized when Saudi grades of crude oil are used. As the speed of the transition to alternative and greener sources of energy is accelerating, Riyadh seeks to turn China into its safety net against the decline in Western demand for oil.

The Chinese partnership with Iran comes as a diametrically opposed regional alliance. Perhaps leaving geopolitics aside, China’s attention turned to the Islamic Republic as a way to make use of its petroleum potential – which is similar to the Saudi model. As one of the biggest energy producers, and one which the U.S. is not very satisfied with, Iran can help China formulate trade routes that cannot be disrupted by the U.S. Iran is out of tune with the rest of the MENA states – its agenda and the policies it pursues suggest an incoherence with the rest of the region, which is exactly what China wishes to use in order to insulate itself from American influence in the region, however minimal this has turned to become.

China’s great game in the Middle East, therefore, is not a single regional strategy, but a wide portfolio of investments. The potential that the oil reserves have, is an eye-catching deal that the Chinese cannot walk away from, hence the main destination of Chinese investments in MENA is in the energy sector and this accounts for more than 47% of all investments in the region. The geographical position of the region is an asset and a factor that makes China unwilling to devote attention elsewhere. The CCP’s “China’s Arab Policy Paper” published in 2016 showcases the devotion to the region and the systematic efforts to secure its growing energy interests. Even though this relationship is a fledgling one, the potential for both partners is immense.

When it comes to Africa, the image changes. Africa has become the fastest urbanizing region of the world, according to McKinsey’s “Lions on the Move II” 2016 report. Rural and internal migrants are moving into cities at a rate that has even surpassed that of China and India. As the continent finds itself caught up in the wave of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the challenges that emerge clash with the opportunities that this process is offering. It was China that answered the continent’s call for investment in infrastructure and new technologies – and the pace of these changes keeps accelerating and becoming more and more surprising.

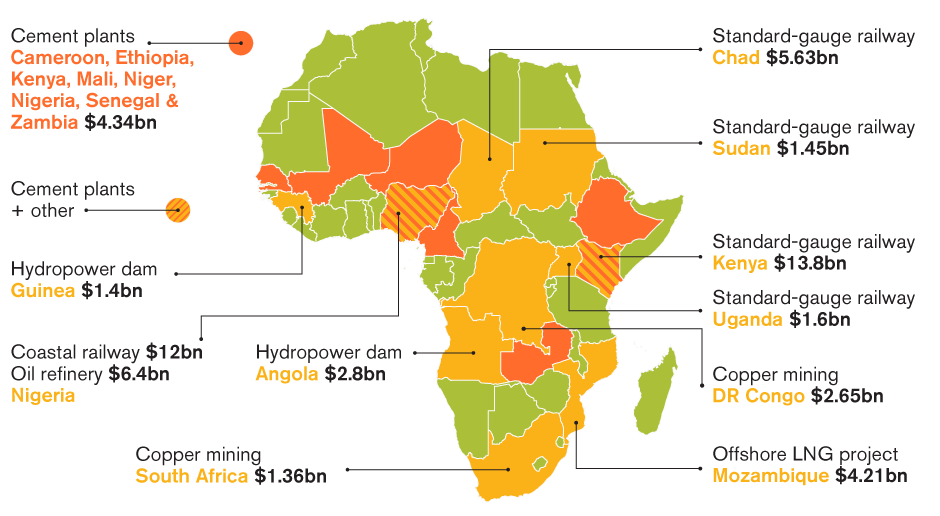

The accelerating pace of urbanization carries several challenges with it, even though it is taking place in the world’s second-fastest-growing region. A large number of the region’s infrastructure initiatives are being supported by Chinese companies and/or funding. Even before the Belt and Road initiative was formally set in motion in 2013, Chinese companies played a central role in Africa’s urban development sphere. Soon after the Chinese Communist Party consolidated its power, it started making political commitments to one country at a time. These included building railroads, hospitals, universities, and stadiums throughout the continent. And even though the former colonial titans were shifting their attention from the region, the plethora of natural resources was still capturing China’s attention – the wealth of minerals, forests, wildlife, arable land, water, and oil made China waste no time to step in the power vacuum and outline beneficial policies centered on this natural richness.

Today, China is Africa’s most important trading partner, with the trade between the African continent and Beijing topping $200bn per year. Over 10,000 Chinese-owned firms are currently operating in the African continent, according to McKinsey, and more than $300bn in investment is on the table. Africa is an even greater trading partner than Asia when it comes to overseas construction contracts. In 2019, China announced an even more fortified and greatly enhanced Belt and Road Africa infrastructure development fund and aid package.

China’s role is a central one – without Beijing, the African states would have to collectively spend $130-170bn per year to cover their infrastructure needs, which is reduced to almost 40% when China is added to the equation. China is the great player that managed to overcome Africa’s infrastructure, urbanization, and service gap, bringing to the continent railroads, highways, and airports. China is positioned to cover the continent’s greatest need – the need for better infrastructure. This infrastructure-infused growth is the type of economic growth that Africa is looking for right now, and China is bringing the necessary technical and financial support for this process.

This does not come without a price, however. Chasing dreams of better economic prospects and development for many African states means burying themselves under layers and layers of infrastructure-induced debt. In Ethiopia, the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway led to Ethiopia devoting almost ¼ of its total budget in 2016 to cover the costs of this project, while in Kenya, the highway from Mombasa to Nairobi cost the country 6% of its 2018 GDP, even though the project was financed 80% by China.

Africa is not a single, frictionless, economic unit similar to China, and it should not be treated as such. It is not a single market, and the heterogeneity that characterizes African states is something that decision-makers should always take into consideration. The rate at which Africa will be able to match the pace of Chinese investments, and the degree to which they will be harmonized into the different domestic settings is a delicate process. When it comes to investments, things are not black or white – adaptation and incorporation come in phases.

Overall, it can be easily seen that China is aiming for nothing else but involvement without entanglement. Regional politics in both the African continent and the MENA carry with them a myriad of issues, which would divert attention from China’s essential aims. Both regions are central in the formulation of a decisive – and sometimes aggressive – foreign policy, which makes the West regard China as a real threat to their security, political and economic interests. Perhaps what China is doing, however, is nothing else other than attempting to redefine the status quo and reset previously established regional imbalances. The outcomes of these processes will be felt slowly, but surely not without impact.

References

- China’s great game in the Middle East, ecfr, Available here

- Chinese investment in Africa: New model for economic development or business as usual?, doc-research, Available here

- MENA at the center of the West: China’s “opening up to the West” strategy, mei, Available here

- Why substantial FDI is flowing into Africa, blogs.lse.ac, Available here