By Socratis Santik Oglou,

The French New Wave

The term New Wave —La Nouvelle Vague— takes place around the 1960s, and covers a wide range of directors, many of whom have nothing in common with each other. But, while this movement is not particularly compact, the removal of any narrative conventions that characterized cinema at the time, as well as absolute artistic and thematic independence, which often reached the extremes of eccentricity, are commonplace in his works. The works of the movement are characterized by a maelstrom of philosophical basis —from the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus— and on the other hand by a detached unconstitutional approach to things which alludes to Bertolt Brecht. Unexpected and irrational deaths and suicides occur in the New Wave film for which there is no preparation or explanation. The protagonists’ decisions appear arbitrary, while the environment around them is devoid of logic and equality.

Simultaneously, there is ongoing experimentation with cinematic methods that leads to a complete overthrow and reorganization of cinematic codes: new wave directors’ films are replete with references to Vigo, Bogart, Hitchcock, Hawkes, and Renoir, as well as elliptical unorthodox approaches. Space and time are arranged according to the director’s and his heroes’ wants, rather than the sequel’s necessities. The narrative laxity speaks more to the new novel than to the “well-made work”, to which he adheres to classical dramaturgy principles.

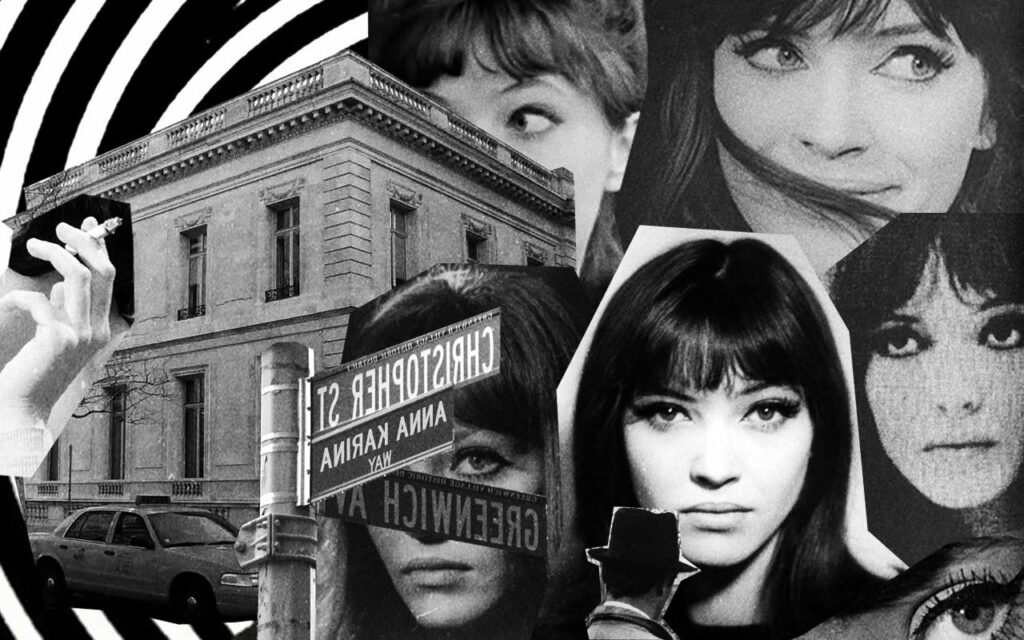

Anna Karina

Anna Karina (born Hanne Karin Bayer, 1940-2019) was a Danish-French avant-garde film industry persona. In the 1960s, she worked with French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard, appearing in numerous of his films, including “The Little Soldier”, “A Woman Is a Woman”, “My Life to Live”, “Bande à part”, “Pierrot le Fou”, and “Alphaville”. Karina won the Silver Bear Award for Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival.

She arrived in Paris at the age of 17 with barely any money and no knowledge of the French language. She was approached by a woman from an advertising firm who requested her to take some shots while she was seated at the café Les Deux Magots one day. She began working as a model and quickly rose to prominence, posing for numerous big publications and ads. Karina and Godard started dating while working on “Le Petit Soldat”, and they married in 1961. Karina eventually became Godard’s cinematic muse. She remarried three times after her divorce from Godard: from 1968 to 1974, she was married to French actors Pierre Fabre and Daniel Duval, and from 1978 to 1981, she was married to American film director Dennis Berry.

Karina constitutes an iconic figure of 1960s cinema, a style icon, a staple in the French New Wave movement. “Her 60s French girl style –think sailor dresses, tartan, long socks, and hats– and mesmerizing doe-eyed beauty mean she continues to be referenced today by the super-stylish,” wrote Refinery29. Her short black hair, bangs, heavy eyeliner, school uniform with knee-high socks, and her berets became her defining, iconic style that everyone recognizes.

“Breathless”

Someone could say that “Breathless” —À bout de souffle— was the film that introduces the New Wave in the late 1950s. The plot has Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a small-time crook, nonchalantly killing a cop. He travels to Paris to obtain money to flee the country when at the same time he tries to persuade his American girlfriend Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg) to follow him, but she is less willing to do so. When Michel has finally got the money he needs and he is about to flee the city, Patricia betrays him to the cops, which leads to him being shot as he tries to flee half-heartedly.

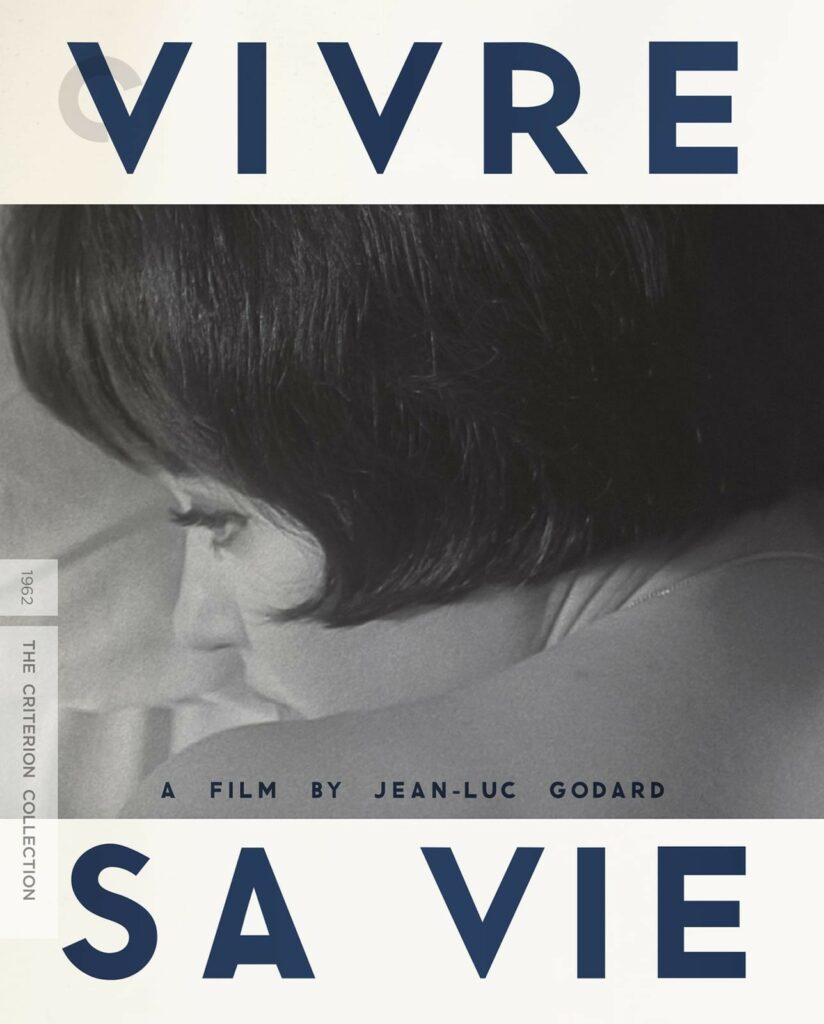

“Vivre Sa Vie”

Godard’s fourth film, released in 1962, opens with a long sequence between Nana and her ex-husband, in which the two talk behind the camera. Most of the times Nana is short of cash while she desires to live life to the fullest. As a result, she becomes a prostitute on purpose.

Her story is structured into twelve tableaux, each with an inter-title that functions as a chapter heading. The plot is broken up in this way to offer the necessary Brechtian distance. Her whole life is a series of seemingly random plot twists and ups and downs, with her decisions leading her to her sudden death. The ending is shocking, but it is unavoidable.

Starring Anna Karina, in my opinion, is one of the most gorgeous, sensuous, and iconic actresses in film history. You will see in the role of Nana going on an emotional roller coaster exhibiting her emotions, while you will see her feeling herself around a barroom in a crazy dance while she tries to seduce her to-be lover. There is also the beauty of Paris, with the stunningly photography of cinematographer Raoul Coutard. Along the way, there’s literature, mainly Poe’s “The Oval Portrait”, philosophy —a Socratic debate with Brice Parain—, music — Michel Legrand’s powerful, minimal score.

Godard said that this was the first film in which he did not worry about the shot arrangement and simply set up and called action. A film to watch.

References