By Anastasia Miskaki,

The curse of artists that pass away young has always been a rather dark yet mesmerizing aspect of fame. Several musicians, actors, and even writers who died early have been and are still being immortalized as tragic figures, struck by misfortune or the repercussions of an early rise to fame. One cannot help but think of Club 27, for example, with Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse, Kurt Cobain, and Robert Johnson, who famously sold his soul to the Devil to achieve musical success, among some of its known members. However, what most people often fail to see is that the cult of the tragic genius individual has older origins.

One of the first modern figures to be considered an artistic genius tragically lost is 18th-century poet Tomas Chatterton. Chatterton’s story has rather been forgotten now, but in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, he almost acquired the status of celebrity, mostly due to his supposedly committing suicide at the age of 17. The young boy and his tempestuous life had a profound effect on posthumous writers. Romantic poet John Keats dedicated his poem Endymion (1817) to Chatterton, while other renowned Romantics, such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley penned poetry inspired by Chatterton’s short yet turbulent life.

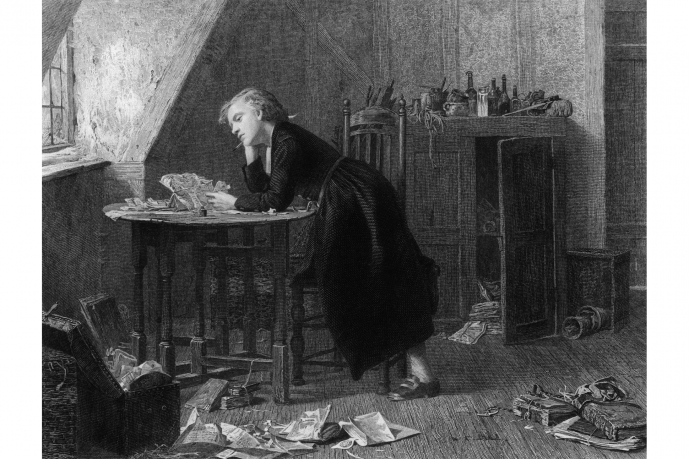

So who was Thomas Chatterton? And why is his case so interesting? The bizarre thing about this figure is that to understand the significance of his life we should look at it from two perspectives: one focusing on his actual life, and one on the aftermath of his death. On the cold night of November 20th, 1752, Thomas Chatterton, son of Thomas, a rather peculiar schoolmaster, and Sarah, already a mother of one, was born. Chatterton was born in Bristol, England, where he passed his early childhood as a child supposedly slow at learning how to read and write. The young boy was very soon fascinated by the church of Saint Mary in the parish of Radcliff, where he often came across old documents that recorded the long history of the Gothic building. When he was 8, Chatterton was sent to a charitable foundation, Colston’s, to receive his vocational training on commerce and law until he was later employed as a copy clerk. What his employer would soon discover, however, is that the child spent his free time composing poems, for which he was beaten repeatedly. That did not seem to stop young Chatterton, as he began to read and produce more literature, culminating in the publication of a poem in the Bristolian newspaper Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal in 1768, when the boy was only 16. But, what is compelling about Chatterton is that apart from a poet, he was also a forger. The young prodigy must have discovered the figure of Thomas Rowley, a 15th-century sheriff of Bristol who he then recreated as the main literary persona of his works.

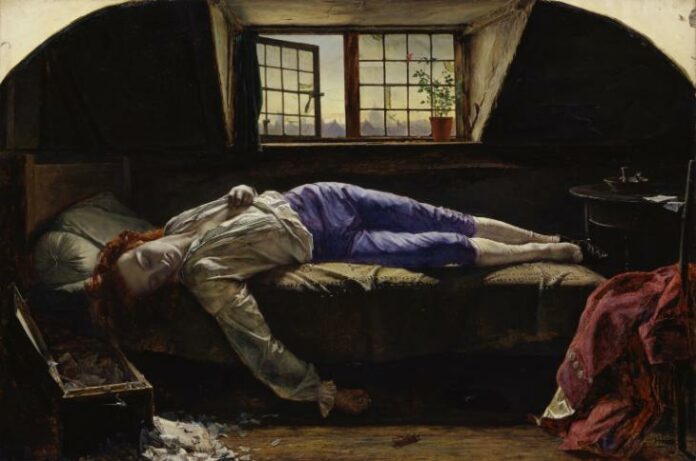

Essentially, Chatterton wrote poems set in Anglo-Saxon or medieval England, but presented them as original, “found” manuscripts written by Rowley and locked for years inside the church of St Mary. Soon enough, these invented texts grabbed the attention of local antiquarians, who were genuinely interested in seeing more of what the young boy could unearth. As soon as Chatterton realized the potential of his forgeries, he began seeking a patron that would offer both financial security, as well as ample literary space for him to continue creating and explore his Rowley universe. Horace Walpole, author of The Castle of Otranto (1764) was initially interested in printing the Rowley poems Chatterton would feed him little by little, but fairly quickly uncovered the truth. What followed was a clash between Walpole, a member of the aristocracy, and Chatterton, representative of the poorer classes. Following this and another Rowley publication, Chatterton decided to leave for London in 1769, in order to find fame and inspiration. Things were indeed looking up for the young genius. Chatterton managed to establish connections with several important London publishers and editors, and write more prolifically under his own name (or sometimes under the nom de plume Decimus), contributing political letters, eclogues, and satires to various newspapers and magazines. However, the money he gained from such endeavors was evidently not enough to support Chatterton’s at times rather demanding lifestyle. In fact, there were times that Chatterton starved and refused to accept any help. On August 24, 1770, while he was in his attic on Brook Street, Chatterton tore apart some of his manuscripts and afterward drunk arsenic. Although there are those that speculate the boy had been prescribed arsenic for venereal disease, the one question we should ponder upon is, what do Chatterton’s life and death mean exactly?

Chatterton reworked and rewrote history and, naturally, this did not sit well with quite a few people at the time. The young poet actually rose to prominence after his early death when the forgeries started to be included in different literary collections. The mere nature of his writings as supposedly original medieval literature is what caused a long controversy in the form of various pamphlets and tracts. However, what made Chatterton even more famous was his role as the ultimate genius – poet for his successors – the Romantics. William Wordsworth famously described him as “the marvelous Boy, “The sleepless Soul that perished in his pride”. Alfred de Vigny a French Romantic, wrote Stello and Chatterton, both of which recount the poet’s short life around the middle of the 19th century, and, more recently, in 1987 Peter Ackroyd wrote Chatterton, a novel that narrates the poet’s life from a more philosophical perspective.

Clearly, then, Chatterton was an interesting case of a writer. He was a poet, a forger, a historian, an antiquarian, a firm believer in the power of the past. Genuinely interested in bringing at the forefront not only the history of his hometown, Bristol, but the general history of England, I believe Chatterton played a significant role in how we see the past, how we perceive people who died young as well as how we view geniuses.

References

POETRY FOUNDATION, THOMAS CHATTERTON. Available here