By Ana López Usó,

The Oxford Dictionary defines poetry as “literary work in which the expression of feelings and ideas is given intensity by the use of distinctive style and rhythm”.

Poetry is the oldest form of literature. The first traces of poetry are found during prehistorical times with the creation of hunting hymns. In medieval times, it was present in the shape of songs sung by troubadours. With the invention of printing, it adapted to written text, and acquired fame and prestige, upgrading to literature’s best-regarded genre. Poetry has known how to adapt to different times, and now, in our fast-changing technology-based times, it keeps doing so. In a society where the online world is gaining presence at a reckless speed, poetry has made its way to social media, specifically Instagram, producing the concept of “Instagram poetry”.

The term “Instapoetry” serves to define the literary style emerged online, however, the authors of such works do not use the term of “Instapoets” as they defend their work is regular poetry merely shared on a social media platform. However, Instapoetry does present many differences to the traditional gerne of poetry, a distinction that made some critics define it as a “new (sub)genre”.

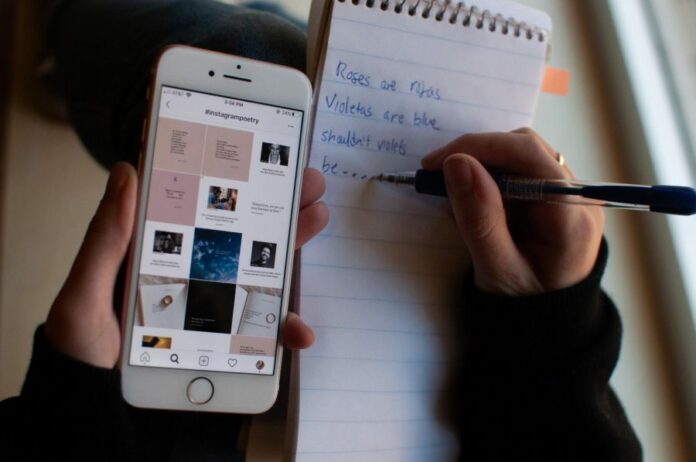

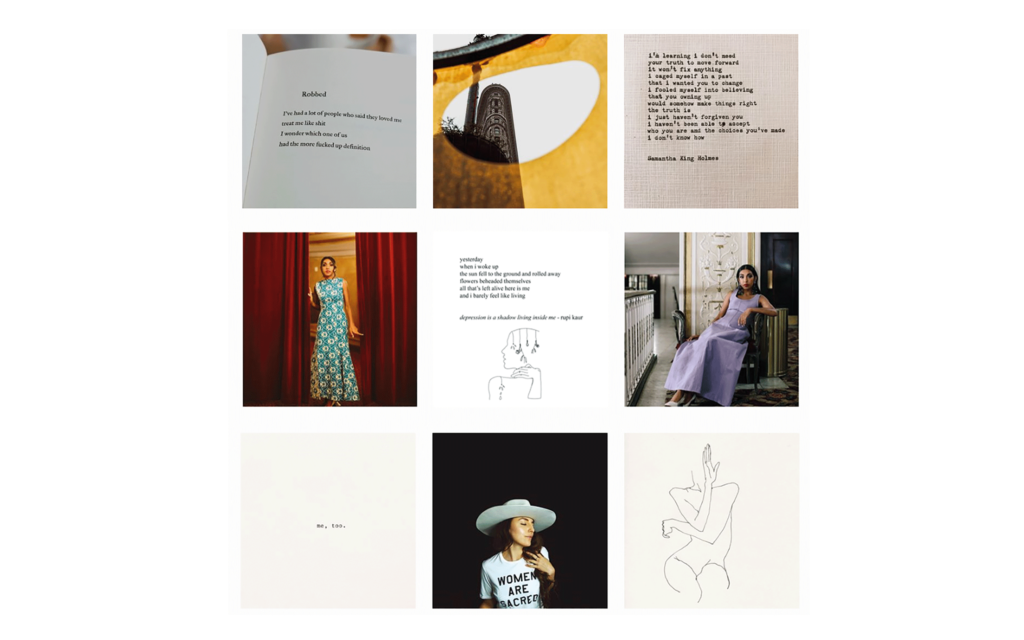

To begin with, Instapoetry is characterized by simplicity. Free verse, very short sentences (sometimes of three words or even one), lack of capitalization or punctuation, and very direct messages are some of the main features of Instagram poetry. But the differences do not end there. What Instagram poetry is more known for is the use of different visual elements to appeal to the reader. The most obvious ones are the use of images and illustrations, but also the use of specific colours to convey different meanings: light and warm colours to portray a sense of calmness, different shades of grey and black to emphasize feelings of sadness or despair, use of textures and fonts to give a sense of tradition, realism and depth to the poems, etc. In the article “The Handwritten Styles of Instagram Poetry” (2019) the scholar Seth Perlow highlights the singular use of handwriting font in Instapoetry: “Instagram poets join a long tradition that views handwriting as heightening the lyrical intensities of a poem, its status as an intimate, affectively rich expression of the poet’s thoughts and feelings”. Poets know how to make an impression on the reader and they are making vastly use of it.

Either way, this method of doing poetry has shown to be effective. One of the most famous instapoets, Rupi Kaur, has as many as as 3.5 million followers on Instagram. Fellow writers also present very high numbers of followers such as R.M. Drake with 1.9 million and Atticus with 1 million, among others. Yet, not only in the online world is Instagram poetry a success, it has also proven to be effective in the literary market. With her first book “Milk and Honey”, a collection of the poems she had been posting on Instagram, Kaur sold up to 1 million copies the first year, surpassing by far the bestselling traditional poetry title Devotions, by Mary Oliver, which sold 36,000 copies.

However, the revolution caused by Intapoetry in the literary world has not been exempt of criticism, with as many supporters as it has detractors. Among the many aspects of Instagram poetry that are being debated, the main subject is quality. The characteristic simplicity of the genre is the main target of criticism. The poet Rebecca Watts decried Instagram poetry as being an “open denigration of intellectual engagement and rejection of craft”. The poet Patricia Smith stated that she is “not interested in writing short bite-sized pieces that can fit into a square on Instagram”, and draws a contrast between the “quick and digestible” work in Instagram and the traditional “poems that people get to marinate on for a while”.

On the other hand, supporters defend that this style, as it is more direct, clearer, makes use of less figurative language andrather depends more on visual aid, is easier to understand and consequently, is targeted to a wider public, as everyone can feel related to it. Ian Williams, award-winning poet and professor at the University of British Columbia stated:

“For a long time, poems have been so difficult and rarefied […] (Kaur) seems to be flouting convention. Her readers can understand what she’s talking about. They don’t feel insulted or stupid, and they don’t feel like they need to dissect [the writing] like in English class.”

This takes us to the second topic of debate, Instagram poet’s success. The exceptional embrace of Instagram poetry does not only rely on the author’s words, but there are many other factors that contribute to their popularity. For example, the work of these authors cannot be based in one specific poem, but the arrangement of an Instapoet’s whole page is crucial for the understanding of their work. This is the reason why many critics and fellow poets have accused Instagram poets of being a “brand”. Poet and essayist Claire Fallon, for instance, calls the environment of Instagram poets a “huckster’s paradise of self-promotion and media manipulation”, putting consequently into doubt their portrayal as “open” and “authentic”. The poet Rebecca Watts shared this opinion by defining Instagram poet Hollie McNish’s work as that not of a poet, “but of a personality”.

However, Instagram poetry’s popularity does not seem to slow down, neither on the social platform, nor in sales lists. Rachael Allen, editor of the poetry magazine Granta, explained why she does not find the rise of Insta-poetry alarming. According to her, Granta is still getting about 2,000 poetry submissions per year. “I think it just goes to show that all these ways of reading are able to coexist with each other quite peacefully”, she said.

Other supporters, as professor Timothy Yu, defend that the genre of Instapoetry has saved an “ostensibly moribund genre”, as it is “drawing new audiences”. Others state how Instagram poetry could be used as incentive for students to read and write, and studies have been done about the relation between Instapoetry and Self-Help (Pâquet, 2019) or its implications on English pedagogy (Kovalik & Curwood, 2019).

Poetry is going to keep changing and adapting as it has done since the beginning of time. Nowadays, and thanks to technology and social media, a large number of the public as we have never seen before has access to poetry and literature. However, as Instapoet Hera Lindsay Bird says: “Poetry belongs to everyone”, and as “it is of everyone”, the question is if the focus of our duty as users should lie in supporting poetry’s development, or in preserving its integrity.

References

- POETRY FOUNDATION: Instagram Poetry and Our Poetry Worlds, διαθέσιμο εδώ

- BRIDGE BEINGS. Using Instapoetry to Encourage Reading & Writing, διαθέσιμο εδώ

- THE ATLANTIC: How Instagram Saved Poetry., διαθέσιμο εδώ

- HUFFPOST Instagram Poetry Is A Huckster’s Paradise, διαθέσιμο εδώ

- POST45. The hand-written styles of Instagram Poetry, διαθέσιμο εδώ