By Ana López Usó,

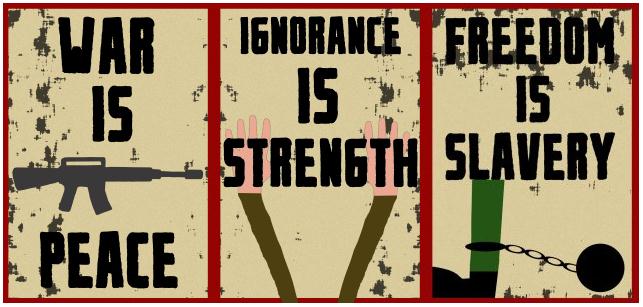

In George Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece “1984”, society is functioning under a totalitarian regime. The leaders of the regime want to eliminate concepts of the known language “Oldspeak” (Standard English) and create a new language, “Newspeak”. The hidden objective behind this process is to make unthinkable every thought that might diverge from totalitarian principles. The new language, Newspeak, is designed to diminish the range of thought by cutting the choice of words and their meaning to the minimum. If the word holds a possibility of more than one meaning, there is a possibility of more than one reality, and that is what the regime wants to end. For example, the word “free” has been reduced to just the meaning of “This dog is free from lice” or “The field is free from weeds”. Since the concept of freedom (freedom of choice, freedom of expression) no longer exists, the regime has eliminated its meaning from language, supressing it, consequentially, from thought as well. There are no negative terms in Newspeak either. The only way of saying something negative is by using prefixes, as the only way of saying “bad” is by saying “ungood.” This way, the notion of “bad” is softened, incomplete, and consequently cannot be used against the regime. Anything the regime does, cannot be “fully bad” but just “not completely good.” In his novel, Orwell achieved to portray a great example of the relation between language and thought, and how the former can influence the latter. Orwell’s society that is ruled by language is fictional, but the line between fiction and reality is not always easy to draw.

An example of how language can really shape thought was presented by Carol Cohn (1987), who, as an international relations scholar, worked for a year next to defence professionals in the field of nuclear weapons during the last stages of the Cold War. Cohn realised how these professionals employed a particular use of language, a very specialised dialect, which she named “technostrategic language”. Technostrategic language was characterised by causing an emotional disconnection in its users, so they could be able to carry on with their jobs, if the time came, facing nuclear war despite the devastation it could cause. Technostrategic language achieved to affect this emotional disconnection by a series of linguistic devices, like the use of euphemisms and abstractions. Terms like “clean bombs” or “limited nuclear war” were used to evoke the idea that these extremely destructive nuclear weapons could cause less damage than they actually did. Other examples on this language was the use of acronyms such as BAMBI to refer to Ballistic Missile Boost Interception, or the use of imagery, referring to bombs as “babies” that are “birthed”, or the extensive use of the verb “to pat” when referring to touching, having or receiving a missile, as if the object of their talk were pets. Furthermore, as in George Orwell’s Newspeak, technostrategic language did not allow for certain ideas or thoughts to be considered. The most notable example was that the idea of “peace” did not exist, with its closest translation being “strategic stability”. According to Cohn, using these linguistic devices turned discussions about nuclear arms, and especially about their consequences, into technical conversations trivialising reality. Cohn defended that her findings demonstrated the possibility of being radically removed from the reality in which people find themselves in, towards a reality that is created through discourse, like she herself experienced: “The more conversations I participated in using this language, the less frightened I was of nuclear war.”

The specific use of language to convey reactions has also been used in politics for many years, creating what is known as “political language”. This topic is widely known in the academic world, and many scholars have engaged into extensive research on it. Noam Chomsky, the MIT linguistic scholar, explained in his work Language and Politics (1988) how “words are the currency of power in political elections”. The characteristics of political language are based on what is called “demagogic rhetoric”, where the objective of a simple sentence is aimed at nothing more than to convince voters. In order to do so, political discourse targets its listeners’ emotions, whether they are positive such as compassion, hope or empathy, or negative like anger or fear. Political discourse is also highly characterised by the use of imagery and metaphors, that tend to be cultural metaphors, to give a false sensation of closeness between politicians and civilians. Another device used to create this sense of closeness is the differentiation of groups, with the reiterated use of “us” and “them”, “we” and “they”, which creates a feeling of belonging and dependence. In another note, political discourse tends to be abstract, never a hundred percent concise, and normally quite simple, because the aim is not that much of telling the exact truth rather than of convincing the listeners that politicians are the ones who know the truth.

George Orwell, in his essay “Politics and the English language” (1946), examined the use of specific words that were already applied in political discourse for very specific aims. For example, he defended that words like phenomenon, element, categorical, primary, and effective were used to dress up simple statements and give an air of scientific impartiality to biased judgements. Adding to that, the use of adjectives such as epoch-making, epic, historic, and unforgettable were used to dignify what he calls “sordid processes of international politics.”

Orwell had a very clear opinion on the specific use of language in order to convince people of certain political ideas, as he portrayed in 1984, and as he stated in his essay: “Political language -and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists- is designed to make lies sound truthful, murder respectable and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

The idea of language being able to shape thought creates the doubt about the extent to which we have power over words, and to what extent words have power over us. In the end, if words are tools used to describe reality, they are also the tools to shape it. Monumental things can be turned into trivial matters, and the most frivolous issues can become the most significant ones. It is not only about what we are being told, but also how we are being told about it. One thing is not to be forgotten; the power of language should never be underestimated.

References

- Cohn, Carol. 1987. “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals”.

- Orwell, George. 1984.

- Orwell, George. 1946. Politics and the English language.

- JSTOR DAILY: The Linguistics of Mass Persuasion: How Politicians Make “Fetch” Happen (Part I). Available here.

- REATCH. How Language Has The Power To Influence Global Politics. Available here.